“You can hear them when they cry and when they laugh, even when they swear. There are no reserves to the talkies. The lady who catches her breath, the lovers who kiss, and the gentleman who blows his nose, even the faint whistle of the man who stutters and tries to conceal it in this way; all are audible to the audience.”

More asphalt: that was the plan for 1928. In the next year or so the Peterborough city council would add two miles of pavement to the city’s streets.

That same year, coincidentally, at least one motor car using those roads, and all the old rudimentary bumpy dirt roads in the surrounding county, added “sound” – and not just the overbearing clamour of a largish engine and heavy wheels. “Fred Imming Can Enjoy Music Wherever He Likes to Go,” stated a headline in the Examiner. “Radio Dealer Instals Set in Motor Car.” Imming, of 5 Cricket Place in East City, owned an auto electric and radio repair shop on Hunter St. W. He surely knew how to combine the technology of mobility with that of communications.

By the mid-1920s the motion picture, now thirty years old, was competing in the realm of amusement with radio, the newest electronic phenomenon of the decade. If they weren’t going out in their cars, people could stay at home and listen to the magic of musical and dramatic programs on their radios.

Capitol Theatre ad, Peterborough Examiner, Aug. 11, 1930, p.9.

Clearly, motion pictures would benefit from spoken words and music and other audible effects too – and adding sound had been an ambition of inventors since the beginning. In the late 1880s Thomas A. Edison had begun trying to find a way of combining the Kinetoscope with his phonograph machine. In the following decades other inventors had come up with machines of various sorts to synchronize sound with film. One year alone – 1908 – had seen the introduction of the Cameraphone, Theatrephone, Chronophone, and Synchroscope, all of them short-lived. In 1909 the Princess Theatorium presented “mechanical talking pictures” – a “first in Peterborough,” said a headline — with an immense phonograph machine set up behind the screen and mechanically synchronized with the projection of the film. The audience saw characters on the screen playing their parts: “those in the audience are convinced that said characters are actually singing or speaking.”

In 1913 and 1914, Edison’s “Kinetophone” – an apparatus for presenting “talking Moving Pictures” – had drawn crowds to the Royal Theatre and Grand Opera House, but for various reasons the device did not meet with lasting success.

Yet despite all the inventive work, fashioning the tools for the synchronization, amplification, and fidelity of sound proved an expensive proposition, and for a long while the end results had not yet been polished to a degree acceptable by audiences.

By the late 1920s, though, the technology was ready for commercial exploitation. Warner Brothers in Hollywood led the way, at least partly in an ultimately successful attempt to break into the realm of the major studios. In 1925 Warner came up with the Vitaphone process, a sound-on-disc system that would change things dramatically. Warner’s first feature “talking picture,” The Jazz Singer, opened in October 1927 in New York City. Although it was actually a hybrid, with only a small part of it sound and the rest silent, it was a huge success. The industry scrambled to catch up; and that took some time because, for one thing, a theatre had to close down temporarily and be rewired for sound – at a considerable cost, from somewhere between $13,000 (U.S., almost $314,000 today) to $16,000 (over $386,000) for a “modest-size theatre.”

It would be almost a year and a half after The Jazz Singer opened before the first “All-Talking Motion Picture” came to Peterborough. (Peterborough businessman Marlow Banks remembered his father taking him to Toronto to see “the first talkie.” He was twelve or thirteen years old.)

In the meantime, with audiences expecting the latest innovations, there was always the phonograph machine. In November 1928, as Motion Picture News reported:

“A talking picture effect was sprung at the Capitol Theatre, Peterborough, Ontario, when Manager J.A. Stewart placed a Brunswick Panatrope behind the screen for the playing of ‘Laugh, Clown, Laugh’ during the presentation of an advance trailer for the feature of the same title. This little stunt caused a lot of ‘talkie’ around town and the film production had three big days.”

The phonograph machine served this role again three months later, on Feb. 9, 1929, when The Jazz Singer did finally come to town – with its reputation preceding it. Although it was not even the partially talking version, Cathleen McCarthy (in the guise of “Jeanette”) suggested that Peterborough movie-goers who went to see it would at least get an “an idea of what ‘the talkies’ will be like when we get moving pictures along the new lines.” When the screen showed Jolson singing his songs – “In his blackface make-up that always suggests comedy” – the audience could hear the same numbers – “the identical words” – with the help of a phonograph placed near the screen.

Even McCarthy, with her demonstrated love of silent pictures, had a tendency to look down on what had come before. In columns that year she repeatedly referred to “the deaf and dumb drama” – employing a common and discriminatory turn of phrase that was conventionally used until at least the 1950s. It was a particularly inappropriate term to apply to the proven artistry of the silent film in the 1920s (although, quite surprisingly, the respected critic Richard Schickel referred to silent film in a 2015 book as “a crippled medium.” Plus ça change).

Despite her affection for the films of the 1920s, Jeanette was looking forward to the end of the era of the “ordinary moving picture performance” in which some audience members “insisted on reading titles aloud or indulging in sound producing foods, such as peanuts or brittle candy.”

By the spring of 1929 and into the summer, theatres all over Ontario were putting in “wire installations.” Famous Players Canadian Corporation, owners of the Capitol Theatre on George Street, announced plans to install sound equipment in 40 of its 130 houses by January 1930. Peterborough would be among the first.

Peterborough Examiner, June 7, 1929, marking the end of the silent film era at the Capitol.

On Thursday, May 30, 1929, after weeks of preparation, the Capitol Theatre proclaimed: “Soon our screen will be heard.” The following day, with an obvious sense of excitement, Jeanette declared (along with a review of the silent Why Be Good? starring Colleen Moore), “The Capitol screen is going to talk for the first time on Monday, June 10th.” Everyone was looking forward to it, she said. A week later she reviewed what would be the Capitol’s last attraction of the era, The Barker (released in December 1928), referring to it as “the swan song" of the silent picture. She found it “entertaining.” But, clearly, it wasn’t enough.

The very next day manager Jack Stewart was being commended (in advance) for bringing “to Peterborough the first talking pictures a short time after their installation in larger centres.” Now, the newspaper noted, “Residents of Peterborough will no longer be able to recite to envious neighbours about the Wonders of the Talkies in Toronto and the queues of people who await their performance. . . . The ‘gabby’ drama is in our midst.” Just in case readers didn't know how it would work, the paper mentioned that the sound effects will “proceed out of the large horns placed on the stage of the theatre.”

That evening, for the feature The Broadway Melody, the Capitol was “packed to capacity” for its two showings, along with a large audience at its afternoon matinee – with ticket prices higher than usual.

Staff members were at the ready. Cashier Margaret Lazure greeted the crowds. Treasurer Peter Scully was there to count the money. Projectionist Harry H. Ristow had no doubt adapted himself to the “New Northern Electric Sound System” (sound films, requiring a constant speed, could no longer be hand-cranked). “The sound picture projector of today is a marvel of intricate apparatus but works as simple as sewing machine,” [sic] said a small piece in the Examiner’s coverage of the event. Ristow also, for perhaps the first time, had a companion alongside him (most likely long-time projectionist Emile Baumer), because now “two experienced men” were “required for attendance in the projection booth, which has been enlarged to take care of the extra equipment.”

The theatre, Jeanette noted, “turned them away” that first day.

“The big screen at the Capitol has vocalised itself and pushed itself a lot farther forward to the front of the stage, in a laudable desire to be seen and heard that gave its watchers and listeners many a thrill yesterday as they listened to its first attempts in a conversational line.”

Peterborough Examiner, June 8, 1929.

Jeanette recorded what she found to be the first words spoken on screen in town. A bullying business man tells off a “lagging” salesman: “I want you to go there and no-one else. Sit down. This is your last chance.” And, she concluded, “With these historic words, the talkies made their debut in Peterborough.”

The lines she quoted came, though, not in Broadway Melody but in an earlier portion of that day’s program, which also consisted of “comedies and short films . . . all being of a conversational variety.” Jeanette described a “delightful little bit of fun” accompanying the feature: a short “Paramount Sound Novelty” that included “a lot of laughing and a lot of jazz shimmying.” Its content reflected that shady bog typified by the long-standing love of minstrel shows, for in it, as Jeanette writes (fully capturing the insidiously racist temper of the times), “a ducky small nigger baby, of the type familiar in the Aesop Film Fables, cavorts through the melody of ‘Old Black Joe’ in a manner that brings applause from a tickled audience.” The crowd in the theatre gladly sang along, apparently, while watching an “animated ping-pong ball” and being led in the beat by “an invisible metronome.”

Certainly, not all went perfectly well with these first talkies (or “movietones,” the term that one Examiner article said was being used). Although Jeanette concluded that “anyone who listens to the screen now, would be sorry to hear it relapse" into its previous state, she complained that the Vitaphone “appears to suffer from an acute attack of tonsilitis” [sic]. She believed that just a little attention to the machine would improve the sound “immensely.” In a review of a film a couple of weeks later she complained that conversations in the features (though not the shorter films) tended to have a “gargling effect.”

Talkies also required a transformation on the part of the audience. Management greeted moviegoers entering the theatre with an unavoidable sign: “Silence is golden.” While loud talking or even yelling out in pleasure or disgust at the pictures might have been perfectly okay in the age of the silents, moviegoers now had to be quiet and make sure that everyone watching could hear the words and sound effects and music bursting out of the horns down front. At the matinee screening, Jeanette found, “The inevitable baby who is such a constant attendant at public performance of all kinds can do a lot to spoil the effect of talking films.” I suspect she was being ironic when she added: “However, the growing youth must be educated and possibly a portion of the upbringing of infants requires their attendance at premieres of talking films.”

Not only that, Jeanette found:

“The successor of the person who used to read the titles aloud from moving films, has been found for the Talkies. She is the lady, or gentleman, who repeats the words of the performers just after they have been spoken, for the benefit of the slightly deaf companion who sits beside her or him.”

Broadway Melody, the first sound film to win an Academy Award for Best Picture, played for a week (uncommon up to that point), three performances daily. According to Jeanette, it held “the rapt attention of its watchers right to the last musical, vivid moment.” Despite his reservations about the coming of sound, the famous French director René Clair pronounced Broadway Melody “a marvel,” especially with its revolutionary technique of having sound replacing what would previously have been done with a shot: “We hear the noise of a door being slammed and a car driving off while we are shown Bessie Love’s anguished face watching from a window.”

By the end of July the Capitol’s manager, Stewart, was pronouncing himself quite pleased with the coming of the talkies. His theatre had not experienced the usual summer slump in attendance – indeed, audience numbers had increased by over 100 per cent since the installation of sound equipment and despite hot weather were growing steadily. The talkies “are taking great,” he said.

“This seems to indicate that Peterborough people like the gabby screen and are interested in the trials, tribulations and joys of the talking actors. The audience seems to live the story to a greater extent that [sic] in the silent versions, it talks, sings, dances and cries with the entertainers.”

Despite Jeanette’s reservations about the technicalities of sound, Stewart held that “The house is built just right for sound” – even though the original “designers had no idea of talkies.” He boasted that the voices and music were being “reproduced in a superior manner to most houses.”

"Long Heralded Talkies Ready at the Capitol, Peterborough Examiner, June 8, 1927.

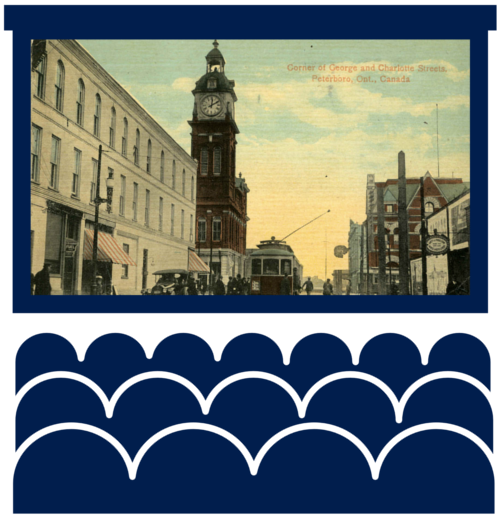

As if to punctuate the transition, too, by mid-September the Capitol was sporting a new flashing neon sign above its entrance, with the theatre’s name spelled out in huge, unmistakable letters – adding, said the Examiner, yet another “bright touch to the evening illumination of Peterborough’s main thoroughfare.” The initiative drew the attention of the U.S. trade magazine Motion Picture News, which saw the efforts of manager Jack Stewart as something quite wondrous (although from their editorial perch in New York City they gave the name of Stewart’s city as “Cedarboro, Ontario”). The theatre’s location near the intersection of Charlotte and George was the place, the magazine said, “where practically all of the traffic from the main highway enters the city.” The new sign had the advantage of “directing attention towards the theatre itself to motorists who are entering the city on other business than amusement.”

The flashy new Capitol sign, c.1930s.

A small group of people in town were not quite so pleased wth the advent of the talkies: the musicians. With sound, the once busy theatre orchestra pits became empty, forlorn places. The days of the “stage show” accompanying motion pictures were also gone (except at the largest movie theatres in big cities). In theatres everywhere, historian Douglas Gomery writes, “Orchestra pits were covered up; paint in the dressing rooms began to peel; and backstage became another storage room.” When the coming of sound was combined with the decline of live attractions at the Grand Opera House, many musicians in Peterborough lost a regular source of work, and income (however small). Writer Donald Crafton, who researched the transition from silent to sound, referred to the phenomenon as the “passing of hometown-generated entertainment,” with the disappearance in the early sound era of “locally specialized forms of entertainments, whether stage shows, talent contests, or singalongs.” The days of the old Royal Theatre’s Thursday evening amateur shows (not to mention the earlier nickelodeon days of illustrated songs with audience participation) were indeed long gone and venues for live performance went into decline – though Peterborough’s “hometown-generated entertainment” never did completely disappear and is in even greater evidence today.