Introduction to

Packed to the Doors: Peterborough Goes to the Movies

Examiner, July 3, 1929, p.12. Although the article has no byline, it was almost certainly written by Cathleen McCarthy, who also wrote movie reviews under the penname of “Jeanette.”

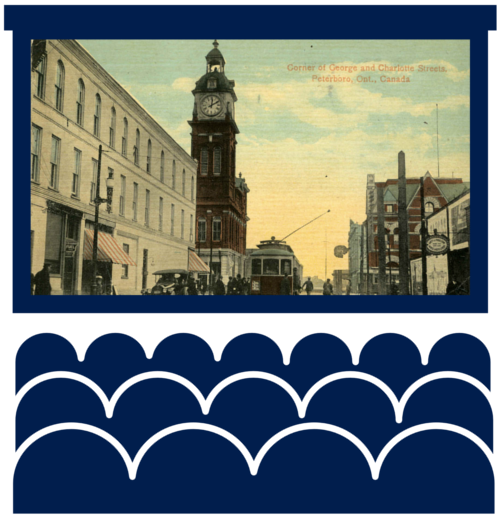

The business and theatre district in 1911, looking south on George Street to the Clock Tower at the corner of George and Charlotte. The Grand Opera House was in the block below Charlotte St.

Peterborough’s “theatre row,” George St. south of Charlotte, August 1954. Peterborough Museum and Archives, P-12-880-1.

Please note: If you would like a quick and brief entry into some of the things I’m doing, in January 2021 I did a talk on my project for the Peterborough Historical Society. Just click on the image.

Let me know what you think. Thanks.

Feb. 23, 2021. Well, it started as a book project and then, thanks largely to my son, became a website project; I’m still hoping for a book eventually. It seems if it makes it into print it might well be two books, one on theatres and one on some of the people involved. The research and writing of a sort continue.

For perhaps more than you ever want to know about me, scroll down this page to a biographical note.

Please do send me your comments, corrections, and suggestions. Try out the Contact page. I’d love to hear from you. You can even make a joke, just like Groucho.

NEW: The story of when Nell Shipman’s film The Girl from God’s Country (1921) came to town, coupled with a short feature about an auto manufacturer trying to set up in Peterborough.

Also, a history of the Paramount Theatre (see “Lives of the Theatres”), and A Paramount Scrapbook (see “Photos and Stories”).

And: a query about the women staffers at the Paramount’s concession stand, 1955.

Peterborough Examiner, May 14, 1962, p.22. Theatres that come with a guarantee!

Rewind: The Electric City Goes to the Movies. The ReFrame film history committee in 2014: from left to right, back row: Michael Eamon, Robert Clarke, Richard Peachey, John Wadland; front row, Eric Lehman, Briar Sutherland, Krista English. Missing: Mickey Renders, Brittany Cadence.

The ReFrame anniversary exhibit takes over the ground floor of the historic Turner Building, corner of George and King, next to the Venue (once the Paramount), 2014. This same building was once neighbour to the Grand Opera House.

“The radio and the telephone

And the movies that we know

May just be passing fancies,

And in time may go !”

The origin of this seemingly never-ending project. And I’m still working on Cathleen McCarthy.

In 2014, for its tenth anniversary celebrations, the ReFrame Peterborough International Film Festival mounted an exhibit, “Rewind: The Electric City Goes to the Movies.” As a member of the team that produced the exhibit, I am following up by researching and writing a book that picks up on that initial project, delving as far as I can go into the social history of Peterborough’s movie-going experience.

I am trying to document all I can find out about where and how Peterboronians saw motion pictures over the past one hundred and twenty-plus years – everything from the first film showing in town (the Lumière cinematographe, in January 1897, at Bradburn’s Opera House) to screenings outdoors in Jackson Park to the rise and fall of the local theatres.

A detail from a larger image, “Peterborough, 1850—1950: A Century of Progress,” by artist Gord Bailey, Examiner, Dec. 3, 1949, p.15: mapping just a few of the amusement-history highlights, including the first motion pictures, 1897, and alongside that, the first television demonstration (presumably in town), 1949.

Examiner, Oct. 12, 1957, p.7. Three movie theatres, a drive-in (closing for the season), radio, and there is always Bingo.

By the way, if you are looking to learn more about Canada’s “rich film heritage” and “the achievements and accomplishments of the men and women that recorded our nation’s cinematic past,” you might want to visit Dale Gervais’s wonderful website, Canadianfilm.ca. In addition to articles taking up various aspects of the country’s filmic past, it includes resources and books you might want to explore.

Moving Picture World, Dec. 31, 1909, p.958.

Peterborough Daily Review, April 23, 1915, p.8. This was during a period in which the word “movie” was spanking new — and under suspicion as being not quite serious enough.

In the late 1940s, for a brief time, Peterborough had five and a half movie theatres downtown (counting the soon to arrive drive-in on the Lakefield Road). “Alfa,” Examiner, July 30, 1948, p.4.

Examiner, Nov. 24, 1961, p.4. An excellent starting list. There were indeed a few others — and it was the “Empire,” not the “Empress” — but it is heartening to know that remembering the theatres of the past is not an entirely lonely pursuit.

The theatres (and other places)

Examiner, March 24, 1962, p.20. The earliest of the city’s film festivals. It was not all about movie theatres. In 1962 the Peterborough Film Council presented its 12th annual festival, held in Queen Mary Public School Auditorium.

The history of the theatres starts with the Bradburn and Grand Opera House (which presented almost as many motion pictures as it did live performances) and moves past the Colloseum, Wonderland, and Crystal (all established in 1907) through the Royal, Regent, Capitol, Centre, Odeon, and Paramount, among others, to today’s Galaxy complex – and including the drive-ins and repertory theatres (such as the Festival Screening Room and the Kaos). Film festivals – from those presented by the Peterborough Film Council as early as November 1950 to Canadian Images, International Images, and the ReFrame Festival – and a short-lived Film Society — are a part of the story too.

The page Peterborough Motion Picture Theatres Through Time provides a chronology of the lives of the theatres.

In 1915 Peterborough had five downtown theatres that movie-lovers could frequent. In 1949 the downtown also had five movie theatres (although that would not be the case for long). In 1962, after the 1961 closure of the Capitol Theatre (and an agreement by Famous Players Canadian and Odeon Theatres (Canada) to “consolidate” arrangements), the city had but two theatres, both managed by Odeon. The movie scene would remain fixed in that way for quite some time.

Examiner, Feb. 21, 1962, p.30. After the 1961 closure of the Capitol, Peterborough’s two theatres, both managed by Odeon Theatres Canada. There was, apparently, a choice: the “Big Show Playhouse” or “Your Best Show Value” (with double features). The management asked: “Do you prefer to see one big movie at a time or a couple on the same program?”

Peterborough’s show people

As an Examiner headline declared over a 1929 story by film reviewer (and society page editor) Cathleen McCarthy, “Peterborough Always Had Lots of Amusements.” And that means lots of stories to tell.

Margaret Howe, at the Centre Theatre box office. Courtesy Bob Howe.

For years I've carried a memory of a woman with an oh-so-familiar face who sold tickets at the downtown theatres. Through my research I’ve found out that her name was Margaret Howe, and she worked in the Paramount and Odeon box offices from 1949 to 1976 (and at the Centre Theatre on George Street before that). No wonder I have always remembered her face. And no wonder too that Margaret’s daughter in law, Mrs. Vina Howe, told me that this was a woman with “personality plus.” The local theatres, from the very first, always had their faithful and capable staff members. The role of cashier was usually seen as a woman’s job; projectionists were almost always men; ushers were usually men, although sometimes (and in the 1950s especially) there were “usherettes.” I'm trying to document these people as much as I can.

I want to record the life and work of “ordinary” people like Margaret Howe and projectionist Emile Baumer – and Walter Noyes (who worked in downtown theatres from roughly 1905 to 1964) – who were, of course, not really so ordinary. And others – like the blacksmiths, cigar merchants, veterinarians, and jewellers who became involved in the business in the early years – and the musicians and other staff members who populated the downtown theatres for decade after decade.

Peterborough Evening Examiner, March 28, 1904, p.4.

Take James Stubbs, for instance. Originally a blacksmith, Stubbs transformed himself into a “lecturer” and well-known local “entertainer.” From his Peterborough base in the last years of the 19th century until around 1915 Stubbs packed up his boxes of equipment — including a Kinetoscope projector, a stereopticon, and a phonograph machine — and went travelling throughout the countryside of Eastern/Central/Southern Ontario. He was one of a handful of touring showmen who marked the early era — in many cases showing motion pictures for the first time to eager rural audiences.

In the city itself, in the years 1905 to 1908 huge crowds went by street car to Jackson Park on the outskirts of town to sit on the grass, eat peanuts, and watch motion pictures “flashed on a large white board supported by stilts.” The all-important projectionist, we are told, was a man named Herb Fife. One evening it seems that the films planned “had gone astray on the road” and did not arrive in time for the screening. Luckily R.M. Roy of the Roy photography studio stepped in to save the day — exhibiting his newest photographic slides – including pictures of the Liftlock, “Peterborough Ben,” “Blind Billy,” and several others

Examiner, Feb. 28, 1939, p.11. Before there was popcorn you could always grab some pie after going to the theatre.

Among theatre owners or managers, the name of Mike Pappas (or Mehail Pappakeriazes) was prominent in the downtown theatre business from 1905 to 1925. At one point in the 1910s a fellow named Herbert Clayton managed three downtown theatres, quite spectacularly; his story, occurring in the Great War years, turned out to have a tragic twist. Then there was George Scott, a Britisher who established the first motion picture theatre in town, in 1907. Unbeknownst to many people, he turned out to have lived a remarkable life both before and after his short stint in Peterborough, becoming what I call “a rare example of the largely lost history of early cinema in Canada.”

Also quite fascinating: the temporary stops of two Jewish theatre owners/managers. Sydney Goldstone (1939–45) and Harry Yudin (1945–55) came to the city in succession to manage the newish Centre Theatre. Both of them added greatly to the variety of filmic fare to be seen in town (at popular prices) – but, just as significantly, they also made important community contributions during the wartime years and after. (Both also happened to live in houses on Gilmour Street in the old west end.)

Examiner, Dec. 17, 1915, p.4. In the mid-1910s downtown Peterborough had four dedicated motion picture theatres (often presenting vaudeville acts as well) — and the Grand Opera House also screened films regularly. With three out of these four theatres advertising Chaplin films.

I’m also intrigued by the pianist and violinist whom the newspapers back in the day used to call “Mrs. Foster.” For many years she played music to accompany silent pictures at pretty much every theatre going in the 1910s and 1920s — the Princess, Empire, Tiz-It, Royal, and Capitol. I finally found out that her full name was Mrs. Eveline Foster, and she lived in Peterborough, often working as a music teacher, until her death in 1968, at age 81. You can see her name on the Peterborough and District Pathway of Fame at Crary Park. Her mother, Mrs. Agnes Foster, also played for silent pictures.

The famous Toronto theatre impresario Ambrose Small – featured in Michael Ondaatje’s novel In the Skin of a Lion – also played a role in town, leaving the scene in a most mysterious fashion. A young police constable and later police chief, Samuel Newhall, enters the narrative a number of times over the first few decades.

In autumn 1907 a young songstress, Miss Edwards, sang “Is there any room in heaven for a little girl like me?” between changes of reels at the Crystal Theatre. In 1914 the Empire Theatre on Charlotte Street screened Tillie’s Punctured Romance starring Hollywood Academy-Award-winning actress Marie Dressler, who was born in Cobourg and first went on the stage in Lindsay.

In 1917, with the Great War on, at least one downtown theatre turned to “lady” managers and “lady” ushers. In the 1920s and 1930s, for well over ten years, the pages of the Examiner featured Cathleen McCarthy, a local pioneering movie reviewer (she used the byline “Jeanette”) — and much, much more in addition to that. As a teenager she worked in a downtown plumbing and electrical supplies shop — and spent her spare nickels going to motion pictures outdoors in Jackson Park and indoors in the new theatoriums of the time: the Crystal and the Royal, among others. She was a phenomenon who lived in Peterborough until her death in the 1980s.

Examiner, Aug. 8, 1949, p.7. Lasting movie memories . . .

Most of this history of moviegoing, of course, I had nothing to do with. I’ve just enjoyed researching the theatres, the people, and the moving pictures displayed on local screens. For some strange reason I especially love the newspaper ads over the years. But as of the late 1940s I do personally enter the picture, to some extent. The first movie memory I can pin down is from the minor film-noir Hollywood feature Impact (1949, with Ella Raines and Brian Donlevy). It played at the relatively new Odeon Theatre on George Street in the second week of August 1949; I was just over five years old. I was transfixed by a couple of scenes in the movie — they remained in my impressionable mind for decades to come, though for the longest time I had no idea what movie they came from. In one of the scenes, someone accidentally broke a vase in a living room — a little boy (me) was apparently so upset about someone breaking a vase that he remembered it for decades. In the other scene I always remembered, two men in a car stopped on a road to change a blown tire; one of them knocked the other on the head with something and rolled the body down a steep slope. Although not knowing what particular movie these scenes belonged to, I did remember that it was “an Ella Raines movie.” It was finally a new technology, the VHS, that allowed me to track the scenes down in the early 1990s, over 40 years later — and they were pretty much just as I remembered them.

. . . and how, in a constant flow, some real living faces got a raw deal

Examiner, April 11, 1958, p.7. A much too well-worn formula. The “Moviexaminer” column began to appear regularly in late 1957. The initials “J.W.S.” appeared at the end of the article.

As someone who came of age, more or less, in the 1950s – with its countless screenings of "Westerns" – I must first of all acknowledge that long before there was Peterborough, with its white settlers, there was Nogojiwanong (“place at the end of rapids”). The land that the invading Europeans took over was the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe or Anishinaabeg, adjacent to Haudenosaunee Territory. About a century later the colonization was formalized with the signing of the Williams Treaties in 1923.

The Indigenous peoples are of key consequence in any history related to motion pictures, primarily because of their (mis)representation in the Westerns and “Indian pictures” that proved so popular for decade after decade of film-going. An early attraction at the city’s first storefront motion picture theatre in 1907 set the tone of the lingering content: Life of a Cowboy (1906), a “stirring western drama,” featured “Cowboys and Indians.” And from then on, as American-Canadian (and half Cherokee) writer Thomas King puts it, “Hollywood has had a long-standing love affair with the Indian.” The love affair was always fraught with problems: unequal and uneasy, a relationship based predominantly on standard but false and damaging stereotypes — and the 1950s especially brought a constant flow of “Westerns” on the screens of town.

Examiner, Jan. 10, 1958, p.7.

Examiner, Feb. 14, 1958, p.7.

Examiner, April 11, 1958, p.7.

Examiner, July 11, 1958, p.7. A regular local review column, “Moviexaminer,” by a staffer. The reviewer recognizes the conventional Western scenarios amidst the entertainment, but has no opinion, it seems, on the offensive treatment of Indigenous peoples.

Typical Saturday morning “kids” offerings in late 1950s Peterborough. Westerns or “cowboy movies” were ubiquitous in the era — and “Indians” were synonymous with war paint and feathers. The racist stereotypes were as widely acceptable as going to church.

Much earlier, in 1911, it was considered to be quite newsworthy when Chief Joseph Whetung of Curve Lake “called into the Examiner” and talked to an editor about earlier days. The editor, a a little surprised, it seems, to have an actual “Indian” walk into the downtown office, took a romantic view of the occasion. But it was the thoroughly embedded age of forced assimilation, of residential schools taking over (and destroying) indigenous lives, of cultural and human genocide. “The Indians have come and gone,” the paper’s writer claimed – which, we can now so readily see, was so very very wrong, in so many ways, despite being in keeping with the endangering sentiment and political purposes of the time. Government policy from the earliest days was to aim at reducing, if not eliminating, the Indigenous population. As Nogojiwanong-Peterborough’s first poet laureate Sarah Lewis, an Anishnaaabe Kwe (Ojibwe/Cree) spoken word artist, said in 2021: “My existence is a form of activism, because we weren’t supposed to be here.”

Examiner, Feb. 25, 1960, p.31.

Examiner, Sept. 5, 1962, p.28. It was not exactly a hidden critique. From time to time articles like these. from 1960 and 1962, would appear in the newspaper to raise the issue of misrepresentation of indigenous peoples.

Examiner, Sept. 6, 1962, p.6. The Examiner editor’s response to the issues raised in the article “Movie, TV Indians Said Leaving Bad Impression” was essentially: let’s just leave it as it is. After all, these characters are treated in the same way as are lawyers and doctors.

A view that persisted for far too long — as if no-one was there . . . as of 1963

Examiner, Feb. 28, 1963, p.19.

And so moviegoing continues . . .

A view from on high of Peterborough’s “Theatre Row,” January 1960. Looking south down George Street, from a perspective up in the Market Hall building on the northeast corner of Charlotte and George. The Capitol, Odeon, and Paramount theatres lined up in a busy downtown. The Capitol is screening The Prodigal, with Lana Turner. From the early days of “opera houses” and the advent of motion picture theatres in 1907, the downtown area was the centre of social and cultural activity – and, despite suburbanization and the loss of these particular movie theatres as fixtures, it remains so today. Still, the city’s distinctive “Theatre Row” itself had only a few more years of life. Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA).

Examiner, May 16, 1964, p.5. TV, postwar suburbanization, and other cultural shifts did not destroy moviegoing, although audiences had declined from the heights of the 1940s. New cinematic styles and (among other things) an “accent on sex,” as exhibited in Tom Jones (U.K.,1963), helped. The audience tended to be youthful, and favourite film fare less than highbrow: the most popular movies of the 1960s in Peterborough were Elvis Presley pictures.

Examiner, Oct. 2, 1961, p.24. With the closing of the Capitol in August 1961, Peterborough had only two downtown theatres (operated by the same company), along with a drive-in (which closed for the season after a midnight show on Oct. 8). But it also had a short-lived film society, which would screen a film a month for the next eight months.

The book will include photos and images I’ve collected, some of which you can see on this website.

As the website evolves I’m adding sections that take up bits and pieces of my research, including “Photos and Stories,” “What’s Doing at the Movies” (which I borrow from the title of a weekly Examiner movie column of the mid-1950s), “Lives of the Theatres,” and “Faces in the Crowd.” You can, for instance, check out items that go a little beyond what might be in a final book, such as “A New Treat Comes to Town, and Receives a Mixed Welcome” (nothing to do with movies); "The Legend of Groucho and the Marx Brothers in Peterborough” (a favourite subject, and discovery) . . . and more . . .

You can help me, too. I am looking for stories, artifacts, and photos about Peterborough’s movie-going history. If you have any, please do let me know.

Thanks, Robert Clarke