Mr. J.H. Larmouth, manager of the Radial Railway Company, has closed negotiations with a New York Company to put on moving pictures at Jackson Park every night except Sunday for two weeks . . . . The machine, which will throw the pictures on a large screen, is known as the Kinetoscope and views will be shown of many pageants, processions and life in various parts of the world. The pictures come highly recommended.

— Peterborough Weekly Review, July 28, 1905

Examiner, April 12, 1905, p.2. Preparation for summer amusements at the park, though no hint yet of “moving pictures.”

In August 1905 in Peterborough it only took a nickel — and eager amusement-seeking people could hop on a trolley that made its way along Charlotte Street, north on Park Street and then west along McDonnel, and eventually up Monaghan Road to Jackson Park. There they could spend an evening listening to the band music and, as darkness fell, watching pictures “flashed on a large white board supported by stilts.” After getting off the trolley car, the passengers would most likely have walked a little north, across Smith Road (then a small dirt country road, now Parkhill). They’d have had to watch out for horses and buggies rather than automobiles as they made their way over and through the gates of Jackson Park proper and up to a relatively flat area (but with a gentle slope, perhaps around where a playground is today).

The opening screening on Monday the 31st of July, as it turned out, took place in “unfavourable weather conditions,” under a threatening sky, but still a “good crowd” came out for the pictures, which were brought in by a representative of the Kinetograph Company of New York. The pictures, said to be “of good variety,” were to be shown again on Tuesday evening, and then with “an entire change in the character of the views shown” on Wednesday. The 57th Regiment Band – the city’s finest and most long-lived – also played.

Morning Times, Aug. 3, 1905, p.1.

On Wednesday, August 2, with better weather, the Examiner reported that “fully 4,000” came out – although another article on a different page the very same day estimated the number of people who made their way to the park at an even more astounding 5,000 (in a city of 14,391 as of autumn 1905). It was “the largest crowd on record at Jackson Park,” the Morning Times stated. “The great part” of the crowd, the Examiner reported, “went up at night to see the moving pictures, and to hear the band.” The report then added another wrinkle in the essence of a summer day’s sweet pursuit of pleasure:

“It is stated on good authority that 400 persons took tea in the park last night. These were made up of small parties who had gone out there by trolley to spend a few hours of the afternoon and take their tea. It is becoming popular for the young lady employees of the large city stores to take their tea at the park, and yesterday two of these pleasing little tea parties took place. At noon the ladies of Messrs. Robt. Fair & Co’s staff went out to the park for lunch, and in the evening the lady members of A.W. Cressman’s staff went to the park for tea and spent the rest of the evening there.”

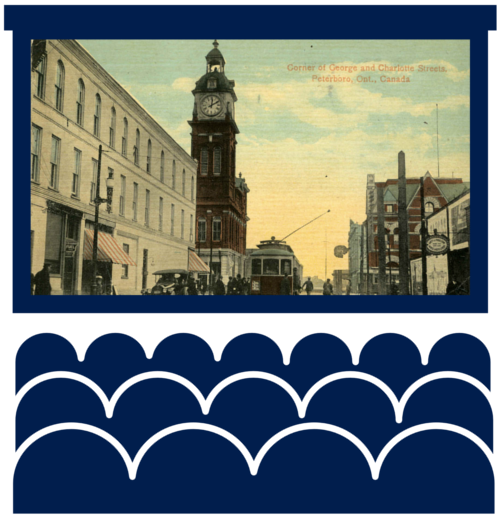

Streetcars on Charlotte, some of which made their way to Jackson Park. Clock Tower in background. Trent Valley Archives.

Alas, although a change of program had been announced for Wednesday evening, “the new pictures had gone astray on the road” and did not arrive in time for the screening. Luckily R.M. Roy himself was able to step in and save the evening from collapsing into complaints or even worse. At the request of the programmers he came along to the park with a supply of several new photographic slides – including pictures of the Liftlock, “Peterborough Ben,” “Blind Billy,” and several others. The Daily Review commented favourably on Roy’s “humorous and colored views.” The management promised that the missing motion pictures would be shown on subsequent evenings, and people who came out would then be able to see something new.

Already, there in the outdoors at Jackson Park, a distinct culture had sprung up around motion pictures: the demand for “new” – as it would ever be in the world of motion pictures, and mass entertainment in general, for that matter. The trick for an exhibitor was established early on: keep people coming back. First of all you had to get the people coming out, and then you needed something different or special to keep them coming back, and back again. . . .

Something they saw that first summer of flickers in Jackson Park: The Lost Child (1904), cinematography by Billy Blitzer, who filmed the more groundbreaking The Great Train Robbery for Edison the year before (1903).

On Wednesday the 16th a brief notice appeared: “New Moving Pictures at Jackson Park this week.” Again that evening the event drew a large crowd, despite “cool air.” The gathering enjoyed a trip through the Alps mountains and The Lost Child (1904) – not a “view” this time, but a “comedy chase” film, the sort of thing that would prove popular for years to come.

When you draw that size of a crowd, trouble is bound to follow. The evening was slightly marred by “a few youngsters” who got into “a little mix-up.” They were reportedly “not behaving as they should.” The large crowds through the summer had not surprisingly led to a few disturbances here and there, and some time before a “special policeman” had been assigned to the park. He took those boys into hand on that Wednesday evening, and all was well. His presence in the park in general “had the desired effect for no one now states that there are any exhibitions of unseemly conduct there.” The boys were later charged with disorderly conduct.

Dog Factory — you have to see it to believe it! Be warned: no dogs were harmed in the making of this moving picture. Library of Congress.

By the end of August the audiences had slackened off a bit, down to about 2,000 on Thursday the 24th. The films that evening included Dog Factory (Edison Mfg. Co., 1904, USA), a comedy about a peculiar shop that turned actual live, but unfortunate, dogs into frankfurters – and that could also, on request, produce real dogs to order (and mayhem ensues). Also on the bill, more notably, was An Impossible Voyage (Méliès, 1904 France), a fantasy film that was a follow-up to Georges Méliès’s famous (and groundbreaking) A Trip to the Moon (1902).

By that point the park had suffered a little from the summer’s activity. It did “not now present the neat and pretty appearance” of the early summer. The grass had turned from green to yellow, with no grass at all in certain spots. The slope where people sat was “littered with paper bags, small boxes and peanut shells” – material evidence of the inexorable connection, from the very beginning, of motion-picture viewing and snacking.

Evening Examiner, July 17, 1906, p.7.

Examiner, July 9, 1907.

Motion pictures at the park continued for several years. Examiner, June 26, 1908, p.8.