A New Treat Comes to Town, and Receives a Mixed Welcome

There was a time – and not so very, very long ago – when Peterborough had ice cream parlours, but no ice cream cones.

Then, one day in mid-June 1908, a “stranger” came to town. Turning up at the corner of Lock and Lansdowne (in the vicinity of today’s massive Memorial Centre), he pitched a tent and set up an open refreshment booth. With the help of “a little gasoline light” that provided a modicum of illumination he was able to remain open for business until about ten o’clock in the evening.

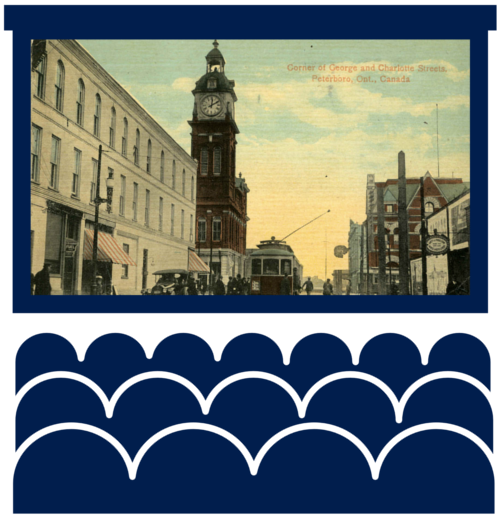

He had probably planned his visit well in advance because the large Cole Brothers circus was coming to town a day or two later and would set itself down in the “Driving Park” nearby (towards Park Street, in the area of what is now Exhibition Park). Indeed, the stranger did such a brisk business that word quickly spread and an Examiner reporter ventured forth to see what was going on there in what was the far, deep south outskirts of town – which was easily accessible by the street railway.

Examiner, June 16, 1908, p.4.

What proved intriguing was the “staple article” of his refreshment booth. It was, the reporter wrote, something called an “Ice Cream Cone” – “a sort of confection.” In 1908 the summer amusement area of Jackson Park and the downtown streets had their popular “ice-cream parlours,” but serving up the treat in a “cone” was apparently an altogether new thing. Indeed, it was apparently so new and unknown that the paper's writer believed that it required a lengthy explanation.

The stranger offered his ice cream in a container “shaped like those old time paper cones in which storekeepers used to put Epsom salts, pepper, etc.” But, unlike those, this cone was “brown in colour and safely contains the ice cream.” Even better, it could be eaten along with the ice cream. The writer described the treat in detail: “The purchaser holds the cone in his hand and begins to eat the combination of course at the big end, slowly doing the disappear[ing] act until even the apex of the cone has been masticated.”

Intense mastication aside, although the article does not go into further details – readers of the time would have been familiar enough with the normal ice cream treat of the time – the seller must have had the usual special bucket-freezer (of tin, pewter, or wood?) or churn with a hand crank. He would have had a supply of ice, crushed into bits or crystals, with some sweetened cream, perhaps some vanilla or other flavouring or fruit, and salt.

Examiner, June 7, 1907, p.7. Peterborough had its fair share of ice cream parlours in the first decade of the twentieth century.

That the writer so carefully went to the trouble of explaining the nature of this peculiar (and tasty) new thing suggests that it was even more of a novelty than other signs of an emerging modernity: a phonograph machine, say, or the rare automobiles seen on the streets, or the new novelty motion pictures viewed downtown in the tiny nickelodeons that had sprung up just the previous year.

Still, although he had done a brisk business with his cones at Lock and Lansdowne, the unnamed stranger had run into a bit of trouble with city authorities. He had come to town hoping to sell his ice cream cones on the downtown streets, but was stymied when he found the city demanding that he pay $30 for a licence. He had considered the possibility of pitching his tent near the outdoor attractions then going on in the city’s summer amusement spot at Jackson Park, also accessible by streetcar, but was not allowed to set up a stand there – “it being stated that merchants of the city must be protected.” As it turned out, he chose to set up his business just outside the city limits, south of Lansdowne Street in North Monaghan.

The man was disgruntled by his Peterborough experience. “The merchants of this city have the place by the legs,” he said, “and it is impossible to do anything without their sanction.” As the reporter noted, “The cone man certainly did not appear to be favourably impressed with the opportunities to transient street pedlars.” The entrepreneur had yet another grievance. When he set out to buy some gasoline for his light fixture he found himself being overcharged. “Why, I had to pay 35 cents a gallon for it up town and away back in Ottawa I only paid 30 cents. Down at the front towns on the lake I could get it for 20 cents.”

Examiner, June 7, 1907, p.7.

The newcomer told the reporter rather boldly that he himself had “introduced the Ice Cream Cone.” Although he may well have launched the treat in Peterborough (given the reporter’s assumption that his readers needed to be told exactly how to go about eating this new confection), ice cream cones had been around for quite some time before that. An 1807 coloured engraving titled “Frascati” (the name of a Paris café) shows a woman enjoying an ice cream cone (though the cone itself was probably made of glass, and inedible). The ice cream cone, like motion pictures, was a delight that had appeared here and there at different times, with no one distinct and verifiable inventor. French cooking books mentioned edible cones as early as 1825. A “cookery book” published in England in 1888 had a recipe for a “Cornet with Cream.” In 1903 a New Yorker named Italo Marchiony took out a patent for a mold for making pastry cups to hold ice cream. For years the small town of Sussex, New Brunswick, professed the distinction of being home to the inventor of the ice cream cone, a baker named Walter Donelly, although this assertion has been disputed.

Examiner, June 15, 1907, p.2. The city fathers did not want the ice cream man to take business away from the downtown parlours and stores.

Peterborough’s larger industrial “electric city” rival, Hamilton, also makes a claim to having produced the first ice cream cones in the country, in 1908. Other accounts tie the confection to the St. Louis World Fair in 1904, when on a very hot day a Syrian immigrant named Ernest Hamwi, trying to sell hot Persian Waffles, joined forces with the man in the booth next to him who was “doing a roaring business in ice cream until he ran out of plates.” Hamwi rolled his waffles into a cone that could hold the ice cream. But, it is said, “at least a half a dozen other vendors at same fair claimed to have originated the ice cream cone.” Another claim to ice cream fame came, interestingly, from Nathan L. Nathanson, the U.S.-born entrepreneur who immigrated to Canada and founded both Famous Players Canadian Corporation in 1921 and twenty years later launched Canadian Odeon Theatres. “I will probably be remembered, Nathanson once recalled, “as the man who brought the ice cream cone to Toronto, which I did.”* That would have been around 1907, when he was operating concession stands at Scarboro Beach Amusement Park.

Towards the end of August 1906, as a teenager, Peterborough’s own Cathleen McCarthy – who would go on to work as a reporter at the Examiner and review motion pictures for the paper – made a trip to visit family members in Toronto. In her diary Cathleen recorded that they went down to the Exhibition – and they had “ice cream cones.”

Nowadays Peterborough has some of the finest ice cream around. July 26, 2018, Toronto.com.

In any case, while the stranger who came to Peterborough in June of 1908 doubtless did not “introduce” the ice cream cone to the world, or even Canada, when the circus came to town the following day, as the reporter said, he was “in his glory” – with no thanks to the “city fathers.”

* The Nathanson quotation is from Paul S. Moore, “Nathan L. Nathanson Introduces Canadian Odeon: Producing National Competition in Film Exhibition,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 12.2 (Fall 2003), p.25.

This piece was published in Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley, vol. 22, no.2, August 2017.