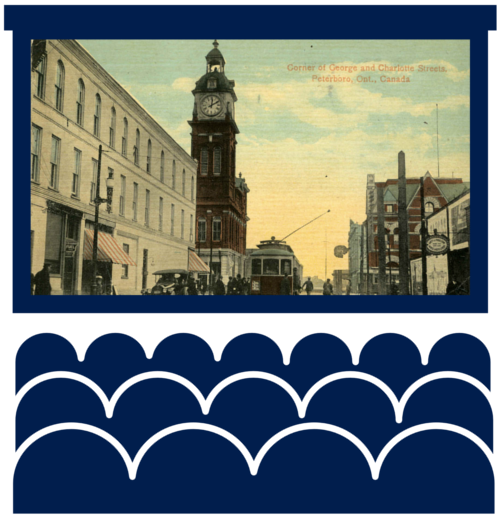

He Was No “Svengali” – but the “Original” Sevengala Came to the Grand Opera House, 1906

Hunter and Water streets, 1906, postcard, Trent Valley Archives, F400.

These days that corner building is home to the St. Veronus Café and Tap Room – a popular spot in the heritage building on the southwest corner of Hunter and Water. Artist studios with their homes on the upper floors and the “Art Crawl” on the first Friday of every month make this a lively place. When this photo was taken, the “Braund Building” was the site of the Canadian Bank of Commerce.

The photographer – perhaps the city’s Louis Mendel – stood a little to the left of centre in the quiet intersection. He took a little time to set up his tripod and camera, and aimed his camera perfectly down Hunter Street. His effort revealed for posterity not just the lavish 19th-century architecture and dirt streets but also sidewalks busy with pedestrians. A man strides across the road – he is glancing our way, perhaps somewhat alarmed at the sight of a camera. A horse, cart, and driver slowly approach the crossing, while further back a horse-drawn wagon with two people on it is about to cross George Street, heading west.

The same shot today – if a photographer dared to stand out in the intersection – would probably document fewer pedestrians and a long line of vehicles waiting impatiently for the lights to change, though you might still see a bicycle resting against the wall of the corner building.

*****

A detail from the Hunter and Water street photo.

Just incidentally the 1906 camera happened to take in most of a poster standing to the left on the corner. The temporary sign announced the engagement of “The Original Sevengala” and “Le Transmission by Telepathy” at the Grand Opera House – and thereby helps to provide a date to this photograph.

“The eminent hypnotist Sevengala” – his real name was Walter C. Mack – was in town for daily performances the week of October 8, 1906, which means this photo was probably taken a little before or maybe even during that time.

Peterborough Examiner, Oct. 5, 1906, p.8.

Examiner, Oct. 5, 1906, p.8.

A news release that appeared in the Examiner on Friday, Oct. 5, reported that Sevengala had spent the past six years in Europe. (Perhaps, like the blustering magician that Dorothy comes across in an opening scene of The Wizard of Oz, he had been performing for the “Crowned Heads”?) That was promotional hype aimed at adding to the mystique of his act: exactly two years earlier, in October 1904, Sevengala was on a U.S. tour – and a release at that time also made the same statement, that he was just returning from Europe. In the year 1900 he had contributed to a book on “Hypnotism and Hypnotic Suggestion” published in New York (suggesting that he was in the States at that time too).

“A Few Words of Advice to Amateurs in Regard to Giving a Public Exhibition,” in Hypnotism and Hypnotic Suggestion, by Thirty Authors, New York, 1900.

From “Professional Cards,” np, in George Fuller Golden, My Lady Vaudeville and Her White Rats, New York, 1909.

In his business card Sevengala made sure to distinguish himself from the better known “Svengali” (a fictional character introduced in 1894). It’s not difficult to see how the two might be confused, and no doubt Sevengala had invented his name with that similarity in mind. “There is BUT ONE Sevengala,” his business card said. All the others were “imposters.” In this he was following a tried and true practice of his trade. A 1901 manual on Stage Hypnosis told would-be practitioners: “What magic there is in a name! If you are plain Brown or Smith, the public cares not for your prowess. You must have an old world name: something that savors on the pyramids, ancient, antique.” Walter C. Mark, of New York City, had chosen his stage name with care.

Hypnotism at the time was a new thing, at least on the travelling vaudeville circuit. The Examiner advised its readers not to be “left behind” in their beliefs: come out and see for yourself – at the “low prices” of 10, 20, or 30 cents – this “king of fun makers” and his “able exposition of telepathy.” While the question of hypnotism might be “much discussed,” it was nevertheless “an established fact, acknowledged by every scientist of the day.”

As the paper put it: “The exhibition of Prof. Sevengala of his wonderful powers of hypnotism is very mystifying to all who witness them. But his greatest feat is the transmission of thought by telepathy, which seems impossible until witnessed by oneself.”

The newspapers disagreed on the size of the audience for the first evening’s show. The Daily Evening Review said it was a “large and appreciative” crowd. The Examiner reported that the turnout was “somewhat small,” though the performance did not “fail to please those who saw and heard it.” The second night also was said to have drawn “only a fair-sized audience.”

Examiner, Oct. 8, 1906, p.4.

Over the week, however, those who came to the opera house had many treats in store for them. Sevengala exhibited different demonstrations – all “clean, bright and original” – with a change of program nightly. In the first part of the program he practised hypnosis on volunteers from the audience, although in truth at least some of the “volunteers” were part of his touring contingent. “Operators” like Sevengala came equipped with a small group of helpers, usually young, who had proven themselves susceptible to hypnosis and could be called upon to perform. But he did also draw some local people forward. In Peterborough one young man proved such a good subject that he was added to the act, joining “the staff” on its future travels.

In the second part of the act Sevengala gave an exhibition of what he called “Le transmission by telepathy.”

After calling for volunteers to come up to the stage, with their complete agreement he hypnotised them and got them to perform various acts. They did things like imagining they were part of John Philip Sousa’s brass band, playing one of that composer’s works with water sprinkling cans, feather dusters, and funnels. (The real Sousa band had appeared at Peterborough’s Bradburn’s Opera House in May 1897.) He had a number of his volunteers go fishing, leaning over and hooking fish from the orchestra seats. One of them took off his shoes and stockings and waded in imaginary water. The audience was “convulsed with laughter.”

Sevengala had been presenting that “fishing act” for a good many years. He had explicitly spelled out its details in the 1900 article:

Great care should be taken in giving the suggestions for a test. For instance, if I wanted a number of subjects to go into a fishing scene, I would suggest in this manner, “Gentlemen, your attention, please. I want you to close your eyes. Now, gentlemen, I want you to try to think of sleep. (Suggest in a very soothing tone.) Think to yourself, ‘I am going to sleep – I am going to sleep – I am becoming drowsy – so sleepy – so tired – s-l-e-e-p-y.’” As their heads begin to nod offer the following suggestions: “As you feel yourself going to sleep, I want you to think of a running stream of water – a brook – s-l-e-e-p-y, let yourselves go sound asleep – A-s-l-e-e-p. When you open your eyes, gentlemen, you will find yourselves upon the banks of a running stream of water; the stream is full of trout; you have organized a fishing party and I will give you $1.00 a pound for all the trout you catch, provided they are not under six inches long. (In a louder but commanding tone) – Gentlemen open your eyes.” In case they do not start right away, I say to them, “See, look at the water – see the fish – you are going fishing – yes you are – come see the water.” The subjects go to the imaginary water, and the rest is easy.

New York State Publishing Co., 1900, reprinted 1906, with Walter C. Mack offering “a few words of advice” for those interested in the art.

In Peterborough’s Grand Opera House the subjects of Sevengala’s spell also went electioneering, roller skating, and honey-hunting. Volunteers became members of a sideshow exhibition – one of them mounted a table and became a “spieler” (or barker), one sold candy, another lemonade, while one man was a sword swallower and another a tight rope walker. “The antics of the young men were ludicrous in the extreme.” All in all, the act “caused the audience great amusement.”

In his telepathy section, after hypnotising a “young lady,” Sevengala went through the audience and gathered, in secret, “commissions” or requests from a number of people. “Without speaking a single word Sevengala raised his hand and the lady carried out the desire of each questioner.” As the newspaper put it, he “asserts that this feature is one which no one on earth except himself is able to carry out, and disclaims mind-reading, which, he says, is simply the use of tricks.” His technique, he confided, was to make “a mental photograph or picture of each thing” requested and transmit it to the young woman by “sympathetic affection of the mind” – with “no verbal communication, cipher signs, code of signals or anything of that character.”

Examiner, Oct. 15, 1906, p.4.

After its week in Peterborough the Sevengala company went on to the Academy of Music theatre in Lindsay – but now with the added feature of a Peterborough boy, Tommie Guerin, having joined the troupe. Guerin had been working as a driver for his father’s butcher shop deliveries, but also had some notoriety as a “local buck and wing dancer” – a form of tap dancing popular in vaudeville. Apparently, when he had volunteered for hypnosis in Peterborough, his actions had resulted in “great amusement.”

Walter C. Mark toured as Sevengala on the vaudeville circuits from around 1904 to 1913, when he died, at about age forty-seven, in New York City.

Sources

Peterborough Evening Examiner; Peterborough Daily Review.

Walter C. Mack, “A Few Words of Advice to Amateurs in Regard to Giving a Public Exhibition,” in Hypnotism and Hypnotic Suggestion, by Thirty Authors, New York, 1900.

Thirty Authors, Hypnotism and Hypnotic Suggestion: A Scientific Treatise on the Uses and Possibilities of Hypnotism, Suggestion and Allied Phenomena, ed. E.V. Neal, 1900; reprinted 1906, edited by E. Virgil Neal and Charles S. Clarke (still with “Thirty Authors”), New York State Publishing Company.

Prof. Leonidas, Stage Hypnotism: A Text Book of Occult Entertainments (Chicago: Bureau of Stage Hypnotism, 1901).

“Notes from the Brennan Amusement Co.,” New York Clipper, Oct. 1, 1904, p.734.

Notice of Sevengala appearance, Watchman Warder (Lindsay, Ont.), Oct. 25, 1906, p.9.

“Joins Independent Circuit,” Variety, Aug. 8, 1908, p.4.

George Fuller Golden, My Lady Vaudeville and Her White Rats, New York, 1909.

“Walter C. Mack,” obituary, Variety, May 9, 1913, p.17.

The undated vintage postcard, Trent Valley Archives, Fonds F400, also appears in Elwood H. Jones and Matthew R. Griffis, Postcards from Peterborough and the Kawarthas (Peterborough: Trent Valley Archives, 2016), p.64.