Bradburn's Opera House, 1876–c1907 and Thereafter

Industries of Canada: Historical and Commercial Sketches,1887, p.57. The Bradburn building, George Street, home to Bradburn’s Opera House. H. Sheppard has a clothing and dry goods shop on the ground floor. An arcade entrance is in the middle. The opera house was on the third floor.

The east side of George Street, 1969, with the Bradburn Building centre left, between Lincoln Shoes and the Market Hall Building. Trent Valley Archives (TVA).

The auditorium of the Bradburn Opera House, 1969, as it remained in its lonely state before demolition began in 1973. Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA). It was in this hall that Peterboronians saw the first motion pictures, among with witnessing many other new technologies, entertainments, and political events. The well-known historian F.H. Dobbin might have been sitting there right in the middle in January 1897.

aka Town Hall, Assembly Hall, Victoria Hall, and “the old opera house”

Town Hall/Bradburn’s Opera House, design plan, 1872. PMA. Once called “Peterborough’s finest public building.” Reduced to rubble in 1973.

The “Times” Business Directory and Book of Reference for the Town and Country of Peterborough, 1876, p.11.

1888—89 Directory of the Town of Peterborough, p.xxv. The Bradburn was already considered “too small for the growth of the amusement-loving population of the town.”

Bradburn’s Opera House, 338 George Street, on the east side above Charlotte, officially opened on the evening of November 13, 1876. It had an auspicious start — featuring a prominent U.S. travelling company led by one of the era’s “stage greats,” Ada Gray, from New York City. The troupe presented The Wanderer on the first night and offered different plays over the following week or so.

With its original grand and lavish structure — and commercial arcade running through the middle of the building from George Street to the back on Market Square — the Bradburn was a point of civic pride. The “Bradburn block,” as an Examiner writer put it in the middle of the following century, “dominated the entire central area of the town and its main street.”

Yet early on, as the 1886—89 town directory pointed out, its small, cramped performance space was considered inadequate for the travelling road show attractions of the time. By the early years of the twentieth century, pressure was on to replace it with a better facility.

A typical night at the opera house. Bradburn’s playbill, October 1897, PMA 98-020.

And it was eventually replaced: when the Grand Opera House opened in autumn of 1905, the days of the Bradburn were over as the city’s prime performance space. Yet it lived on in minor fashion, referred to as an Assembly Hall and for years as Victoria Hall. The space was still there, if in wretched shape, when demolition occurred in 1973—74 to prepare most of the George Street block for the construction of Peterborough Square.

*****

In the years before Bradburn’s Opera House was opened, Peterborough had its meeting places and amusement halls: from Hill’s Music Hall to the Old Methodist Church on the west side of George, above McDonnel (across from where the United Church now stands). [See What’s on at the Movies, Before Cinema: Plenty of Amusements to Be Had.]

Rules of Order and By-Laws of the Town Council of the Town of Peterborough, printed at the “Despatch Office,” Peterborough, 1850.

For decades Peterborough had seen its fair share of attractions, most of them arriving regularly for short stays in town. As early as 1850 town council had passed a by-law to regulate (and benefit financially from) certain commercial events. In that year, for instance, “any person” who came within the city limits to “exhibit publicly . . . any natural or artificial curiosities, Theatrical performance, Circus or other Show or exhibition” had to obtain or pay for a license to do so.” In 1863 council amended the by-law “to make better provisions for the Licensing of Auctioneers, Pedlers, Circuses, Theatres, Shows, Menageries . . . and for fixing the Licenses to be paid.” (Travelling theatrical exhibitions or shows had to pay $5 to $10 a day; an auctioneer resident for the summer had to pay $100; a hawker/pedlar $25 a year.) Circuses made regular appearances, and so too did other special travelling attractions, such as Dan Rice’s “Great Show” (1862) and the “Wonderful Wild Animals” of Dan Castello’s “Moral Exhibition” (1862).

The opera house was the brainchild of Thomas Bradburn (1819—1900) – a so-called “general merchant” who was, according to local historian Francis H. Dobbin, “at that time one of a half-dozen prominent and enterprising men of the town” (and originally a grocer). It was an integral part of a larger project, the Bradburn Building, designed by architect (and town engineer) John E. Belcher with the approval of the town council — and, indeed, it would serve the needs of the council as well as of amusement. The city owned and managed the “Market Hall block” bounded by George, Charlotte, Water, and Simcoe streets, leasing out its various pieces under the jurisdiction of the Peterborough City Trust, established in 1861, and determining rental values.

A glimpse of a long-forgotten stairway in the opera house, as seen in 1969.

As an 1883–84 city directory described it, Bradburn had “erected . . . a fine four-storey [sic] building on George Street, close to the Market Square, the upper flat of which is used as an Opera House. A large amount of money has been expended on the interior fittings, scenery, etc., and very few places of our size can boast of such a well-appointed amusement hall.” The city fathers proclaimed a half-holiday on the day it opened, with the Ada Gray Company appearing on stage that evening.

Just before that, the Old Methodist Church had been a fairly busy place for visiting performers — a week earlier it had featured General Tom Thumb and his wife — but by March 1877 it was being offered for rent.

The architectural drawings, 1872

The "Proposed Town Hall and Opera House, Peterborough" (later Bradburn’s Opera House) was rendered in a series of architectural drawings on linen done by the Peterborough architect, John E. Belcher, in 1872. PMA.

A longitudinal section. Belcher’s signature is in the bottom right corner. The theatre is on the third floor, with the stage on the left end. Belcher also designed the city’s Market Hall and Clock Tower (1888—90) and the Collegiate (1908) and Public Library (1911) in addition to many other local buildings and churches.

A “transverse section,” showing the building’s profile from the side: the three floors, and the theatre’s proscenium arch on the third floor.

A detail from the longitudinal section, showing the theatre and stage. It had a small gallery or row of “loges” along the east side of the auditorium.

The ground floor plan, with the building fronting on George Street and spaces for stores on the street front and along the arcade. Stairways in the middle went up to the second floor.

The second-floor plan (above the ground floor with its shops and arcade) shows various offices, including that of the mayor (on the south side of the building, or top right corner on the drawing), and the town council chambers. The town clerk’s office is north of the council chamber. A wide corridor extended north and south to two sets of stairs leading up to the theatre. As one later account put it: “The public turned to the right on reaching the second floor, and stairs at the opposite and north end of the hallway led to the stage, a private accommodation for the actors, stage employees and any others associated with the business of theatrical productions.” An 1880 inspection found the system of stairways to be poorly designed when it came to emergency exits, and later on they were modified. The Bradburn housed the municipal offices only until the late 1880s. After that the council chambers were used for meetings, parties, dances, and other events.

The third-floor plan, with the stage and hall, ante room, and cloak rooms at each end; dressing rooms on either side of the stage. In his book Early Stages: Theatre in Ontario, 1800-1914 (1990), Robert Fairfield notes: “These splendid drawings now in the Collection of the Peterborough Centennial Museum make up by far the oldest complete set of such documents so far discovered in Ontario, and very possibly in the whole of Canada." PMA MG 1-212 A - Thomas Bradburn fonds.

Peterborough Weekly Review, Jan. 27, 1905, p.5. One of Thomas Bradburn’s sons.

The purposely built features of Bradburn’s Opera House established it as a local institution with staying power. The building was “topped” with a distinctive large cupola and four-faced clock that, the directory said, could “be seen from almost any portion of the town and Ashburnham.” (It was apparently too heavy, though, for the building as structured.) On its street level were shops and an entrance to a central arcade connecting George Street to the Market Square behind. The second floor had municipal offices and council chambers; on the third was the opera house or auditorium, with a “green room and reception rooms.”

Bradburn had undertaken the construction of his building based on an agreement with the municipality to provide offices for the council and civic employees. In 1890, when the town decided to build a Market Hall just next door, the overly heavy clock and bell were moved over to that new edifice. Before that, the space on George Street from the Bradburn building south to the corner had been vacant, used as part of the outdoor market.

Thomas Bradburn’s son William Herbert, a local insurance business agent, took over management in the 1890s, and after his father’s death in 1900 became responsible for the opera house as the estate’s executor. Thomas Bradburn had two other sons: Thomas Evans and Charles Rupert Helm (who went by the name of Rupert). For a while T.E. managed the family’s business in nearby Lindsay (including its opera house, also called Bradburn’s) before returning to Peterborough and going into real estate and insurance as well as local and provincial politics. Rupert engaged in other business enterprises and became manager of the Bradburn in 1902. He left Peterborough for a short time in 1903 to serve as director of the Ottawa Steel Casting Company, but he soon returned and would play an instrumental role in establishing a new theatre.

*****

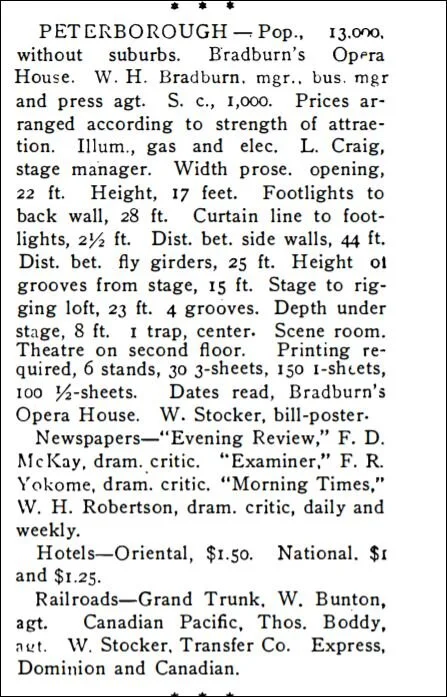

Bradburn’s Opera House had a seating capacity of roughly 1,000; a 1905 description of the theatre said more specifically that “it afforded seats for 400 in the reserved portion, and about 500 in the remainder of the floor space.” Its ticket prices were determined on a case to case basis depending on the “strength” of the attraction. The stage carpenter around the turn of the century was Robert Bradburn, a nephew of the owner.

The width of the theatre’s proscenium opening was on the small side (compared to other opera houses of the time in towns of roughly the same size), at 22 feet, with a height of 17 feet. From the footlights to the back wall of the stage was a distance of 28 feet; from side to side the stage was 44 feet. It was that cramped space which led to problems for the hall.

Morning Times, Aug. 28, 1895, np. Excitement in the opera house arcade.

Although Bradburn’s Opera House has been described as a “lavish” hall with an “aristocratic-looking circle of upper boxes” and “fine curtains,” a writer almost a century later noted, “Rarely, if ever, did it live up to its name.” It was “really an auditorium with a stage.” But in those days every city of any size, once it had its churches and schools established, simply had to have an “opera house.” They were seen “as symbols of advancement and civilization,” as Ann Satherthwaite puts it in her book about the early opera houses. “Here,” she says, “townspeople – men and women, young and old, rich and poor, newcomers and oldtimers – would gather to meet with friends and strangers” and see the varied attractions.

The Julius Cahn’s Official Theatrical Guide 1905—1906 listed forty-three “opera houses” across Canada – even though the sights and sounds of authentic opera were rare indeed in these places. Over time Peterborough would be blessed with two of them (the Bradburn being followed by the Grand Opera House). Aided by its handy railroad connections to west, east, and south, as museum curator and teacher Jon Oldham put it, Peterborough was long able to see “the best of vaudeville in good theatres.”

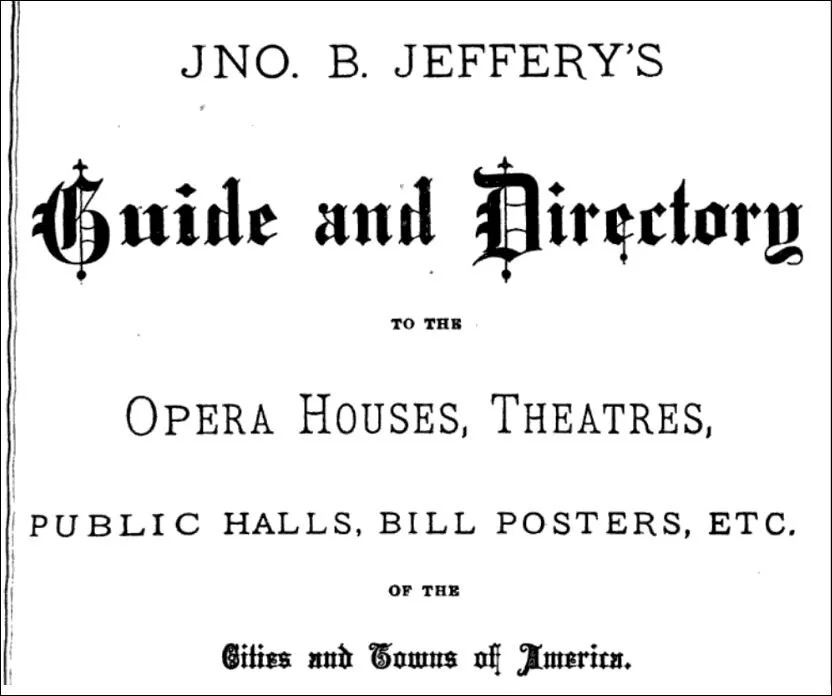

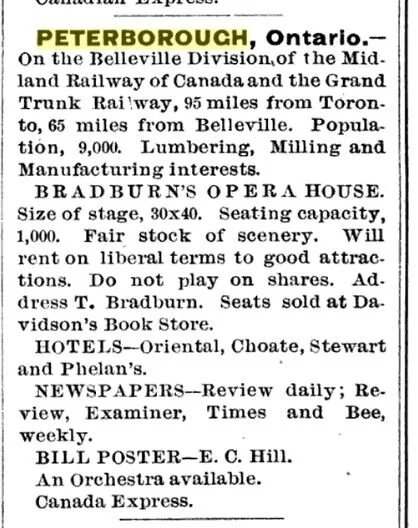

Fifth edition, Chicago, 1882—83.

The Great Theatrical Route: a town on the map

Jeffery's Guide and Directory, 1882—83, p.306.

Julius Cahn's Official Theatrical Guide Containing Information of the Leading Theatres and Attractions in America, vol. 2, New York, 1897, p.40. “Peterboro” on the list of the “best theatrical cities.”

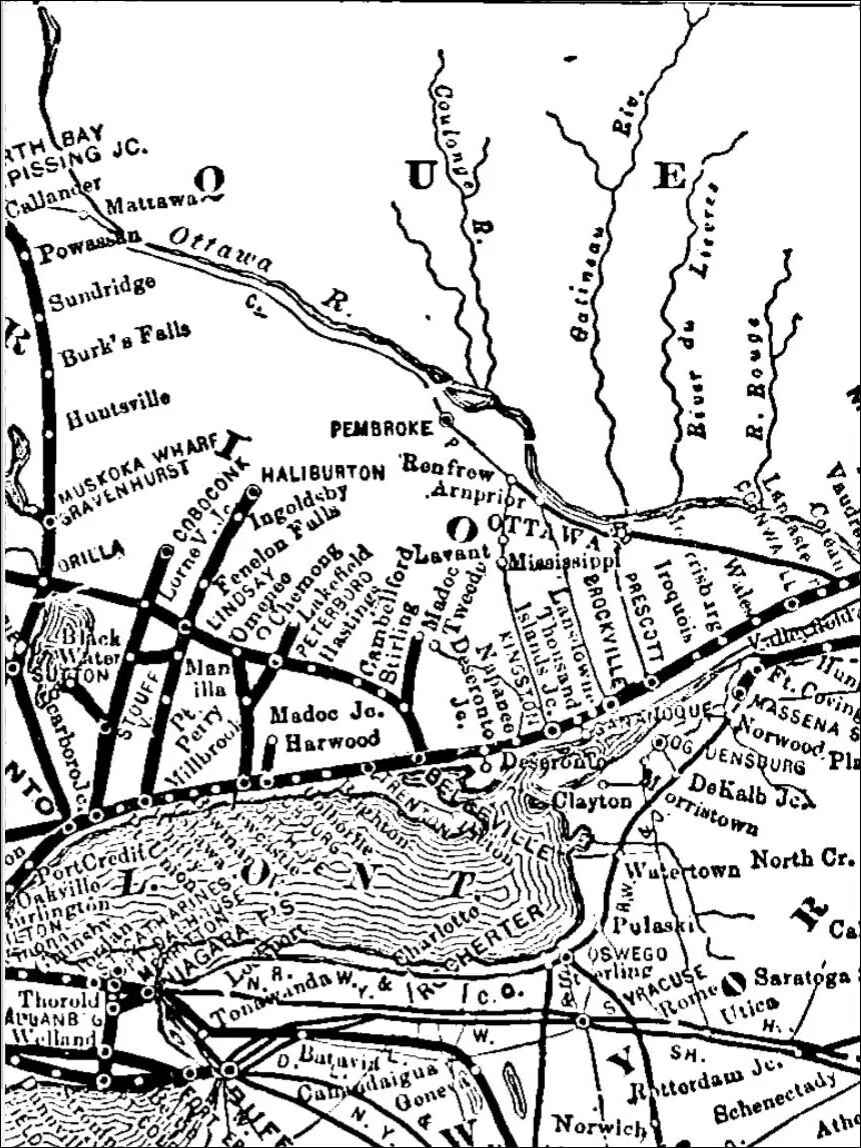

Julius Cahn's Official Theatrical Guide Containing Information of the Leading Theatres and Attractions in America, 1903-04, vol. 8, New York, p.784. A detail from the Grand Trunk Railway System map.

Cahn's Official Theatrical Guide, 1903-04, p.784. A portion of the Grand Trunk Railway System map.

Cahn's Official Theatrical Guide, 1903-04, p.788.

When the English doctor Thomas Bernardo brought the first of his “children” to town in August 1884, he is said to have “addressed an overflow crowd” on the subject of “Waifs and Strays” at the Opera House. In May 1897 the Bradburn attracted the popular band of John Philip Sousa, the U.S. composer and conductor known for his rousing patriotic and military marches. In 1952, as a youngster taken to the movies by my parents in Peterborough, I would learn all about Sousa – or at least the Hollywood version of his life – at the movie Stars and Stripes Forever, featuring Clifton Webb as the bandleader.

Examiner, May 21, 1897, np. Sousa and his band returned to the Grand Opera House, Nov. 22, 1910.

Sousa returns — on screen! Examiner, March 17, 1953, p.7.

Examiner, March 1, 1877, np.

The Bradburn had also seen a steady flow of vaudeville acts, minstrel shows, and the likes of the Marks Brothers, who hailed from Perth, Ont. The Marks Brothers and their various groupings made regular stops while travelling far and wide for decades on the theatrical circuit. The Bradburn welcomed indigenous poet Pauline Johnson (April 1895 and again in May 1903). A young Winston Churchill came along on New Year’s Eve, January 1, 1901 — the first night of the twentieth century, the newspaper called it. His two-hour talk, illustrated with limelight views, covered his recent experiences as a correspondent caught up in the South African/Boer War.

A look back at Churchill’s visit to Peterborough and Bradburn’s Opera House. Examiner, Nov. 30, 1954, p.9.

A local boy, Danny Simon, who went on to a fair bit of fame on the travelling stage circuit, is said to have made his first professional performance in the Bradburn. The country’s leader, Sir John A. Macdonald, delivered a rousing speech to a packed hall in December 1886. The gallery “was filled with ladies,” the Examiner reported. Macdonald told the audience about something that had happened as he mounted the stairs that day on his way to the hall. A local boy had remarked, “There goes the Old Union Jack.” The remark had pleased the prime minister mightily, and the story drew cheers.

The famous boxer John L. Sullivan was in town in April 1894 and made the briefest of appearances on the stage (apparently he was quite shy of audiences). Early exhibitions of those new communications technologies, the telephone (January 1878) and the phonograph machine (June 1878), drew fascinated crowds. In general the hall gave up its space to community affairs and public meetings of all sorts, whether secular, religious, political, or commercial — and to everything from banquets, receptions, balls, and dances to wrestling matches and boxing bouts.

It was a busy place, and after its first couple of decades it was in need of a facelift. Regular attendees were apparently getting tired of seeing “the same old drop scene” time after time, and the same old stage effects used at every performance. Scenic artist Will F. Clarke was brought in to paint new scenery for the stage in 1896; he worked on the stage curtain too, painting “a beautiful representation of Windsor Castle . . . in all its splendour fringed with its summer verdue, the peacefully flowing river in front reflecting the scene on its waters.” The managers added new side and top drapery and five new stage scenes, including a palace scene (which could be mechanically arranged in three different combinations) and a domestic, or “homelike” scene. All would be well for at least a little time after that.

The arrrival of motion pictures

Among the notable events was the introduction of moving pictures in the form of the Lumière brothers’ Cinématographe in January 1897.

Examiner, Jan. 23, 1897, np.

On the cinématographe’s second day in Peterborough two unnamed reporters at rival newspapers described the momentous event – “the triumph of photographic reproduction” – in considerable detail, relating the scenes shown and leaving us with a lasting impression of what it must have been like for those initial audiences to view their first pictures in motion. The presentation had to “be seen to be appreciated,” the Examiner writer said. “If the town knew what it is like the Opera House wouldn’t hold the crowds. It appeals equally to young and old, cultured and illiterate.” The Daily Review writer commented: “Those who have heard nothing about the cinematographe anticipated only the depiction of usual magic lantern scenes upon the canvas. But to those the result will be most astounding.”

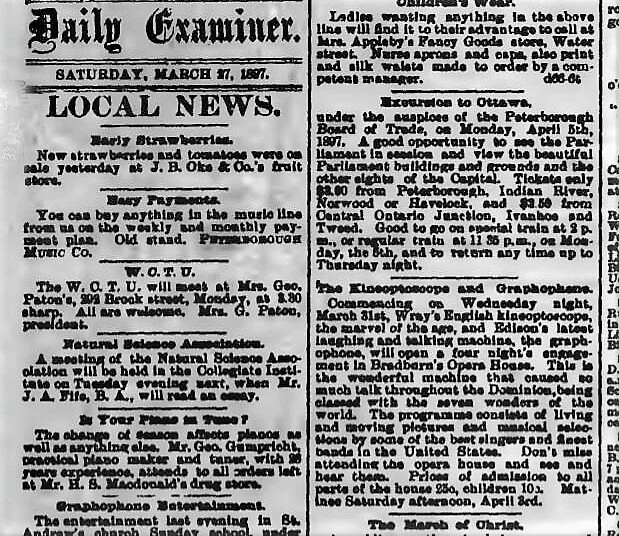

After that motion pictures continued to show up occasionally at Bradburn’s Opera House along with the other more usual fare — including the very next month, March 31, 1897: “Wray’s English kineoptoscope, the marvel of the age, and Edison’s latest laughing and talking machine, the graphophone,” for a four-night engagement.

Examiner, March 10,1898, np. More motion pictures at the Bradburn in the early years.

Above: Examiner, Sept. 10, 1901, p.5. A full season of live performances. The list does not include all the events at the Bradburn that fall: for instance, the “Holy City” event (right), which included “limelight views,” a precursor of the moving picture. It also seems that McEwan, the hypnotist, did not show up.

Examiner, Sept. 18, 1901, p.5.

Examiner, Dec. 6, 1901, p.4.

Examiner, Oct. 8, 1897, np. Sandwiching the live stage event: “moving views” — “the only genuine pictures” of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Procession — and film of a prominent boxing match.

Examiner, Jan. 12, 1903, p.1. Not advertised as “moving pictures,” but as an “Electric Carnival.”

In one interesting case, travelling moving pictures came to the Bradburn without even being advertised as such. Instead it was “an electric carnival.” The January 1903 program, though, presented a variety of short motion pictures of the time (Examiner notices made that clear), including scenes of the recent coronation of King Edward VII, the “eruption of Mount Pelai, and other great events.” Tickets went for 15, 25, and 35 cents, and the event was well attended.

Examiner, Sept. 10, 1902, p.5.

*****

As one century turned into another, Bradburn’s Opera House was still basically intact, and for a time going strong in its own way. The owners made changes: for instance, in the early years of the 20th century the original “handsome and capacious stair case” that led up from the arcade was altered to a stairway somehow providing access to the hall from the south side.

By that time it had become thoroughly accepted that the original opera house – only a quarter of a century old – had “become outmoded and was no longer adequate for the business.” In the early years of the century local worthies were decrying the city’s lack of a proper auditorium. Despite a steady flow of speakers, minstrel shows, concerts, and plays, the opera house was essentially an unappealing place that had “outlived its usefulness” and could not bring in “the very best attractions to draw a large audience.” The theatre could not accommodate the needs of larger companies when it came to scenery and stage effects. As early as April 1902 co-owner Rupert H. Bradburn, apparently feeling the pressure, announced plans for major renovations, including lowering the floor of the opera house one storey and increasing its width to the full extent of the building. He envisaged “modern seats, placed in amphitheatre form,” larger stage accommodations, more “spacious galleries,” and “other improvements.” With a new design along these lines, the Examiner reported, the town would at last see “an opera house which will fully meet all requirements.”

Rupert Bradburn apparently decided against those major renovations. A big issue was a hefty increase in fire insurance rates for the old Bradburn building as a whole — to over 5 per cent per annum — which meant the theatre was considered to be no longer “a paying investment.” Complaints about the facility continued to fester. The Examiner in particular constantly agitated for the construction and equipping of a new first-class, “commodious” building that would suit the city’s needs.

Examiner, Feb. 16, 1903, p.5. The show that broke the Bradburn’s back. It was “packing the Grand Opera House [in Toronto] every night.”

Finally, in late February 1903, Rupert Bradburn instigated major changes to prepare for the arrival of John Philip Sousa’s operetta El Capitan, which was scheduled for March. To accommodate the company he set carpenters to work stripping the stage bare, removing its permanent fixtures (including scenery used over the years), and increasing the size of the platform. He also announced plans to close the opera house down after the Capitan event. “No Opera House,” the Examiner lamented in a headline. “Peterborough Very Likely to be Left Without one of any Kind.”

After that final big travelling show, Bradburn’s Opera House was “out of commission” and “off the show circuit.” The dismantled stage, a writer said, was “hedged in by a hoarding like an excavation for a building in a street.” The Bradburns were soon asking the town council for a reduction in their license fee since the site could only be used for concerts and lectures.

Daily Review, March 23, 1904, p.4. More moving pictures at the Bradburn. This program, from the Bioscope Company of London, England, was presented under the auspices of the local fire department (given one of the key film subjects, the “great Chicago theatre fire”).

Still, the hall did remain more or less in place for the next fifty to sixty years, although seldom if ever used for its original purposes. The performance space – the glorious site of the town’s very first motion picture exhibition – fell on hard times. Notably, for instance, one of the new “electrical exhibits” of 1903 was held across the street in a store. By 1905 the auditorium tended to feature wrestling and boxing events and the odd concert and political event.

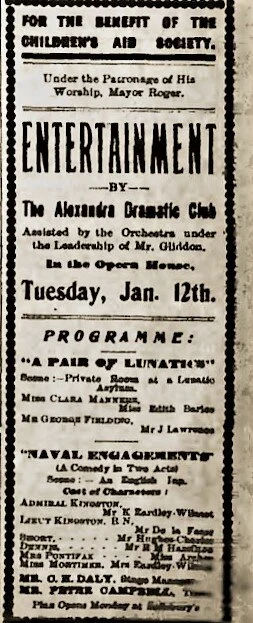

Examiner, Jan. 9, 1904, p.5.

A case in point were two plays staged in January 1904 by the Alexandra Dramatic Club, an amateur group with a Peterborough cast but coached by one C.N. Daly, said to be “late of New York City.” Daly had travelled “a long distance” simply to help out with the performance. A benefit for the Children’s Aid Society, the evening attracted a large but less than capacity audience. Its amateur acting was praised, but the effort suffered from an “almost total lack of scenery of any description.” When the curtain “refused” to work properly during the second play, Daly stepped out onto the stage and delivered “sarcastic remarks regarding the present usefulness of the opera house, its commodious stage and beautiful scenery.” He reflected on the calamity of a recent fire in a Chicago theatre and hoped that if he ever again had a chance to come back to Peterborough “the present opera house would also be burned, without however loss of life, and that the theatre going public of this town would have a new and safe building.” His “caustic remarks evoked ringing applause.”

A Peterborough man who had been to the theatre that evening wrote a letter to the Examiner, signing himself “Humiliated.” He had seen “an excellent pair of plays splendidly produced,” but they had been “cruelly marred by the absence of stage scenery and accessories.” He compared the experience to the “shame” of “receiving a guest in a drawing room furnished something after the manner of a stable.” A town with the “beauty and progressiveness” of Peterborough could do much better.

Examiner, Sept. 16, 1905, p.5. Despite the issues, the Bradburn continued to offer a full slate of events in the fall of 1905.

Around that same time an Examiner editorial opined: “The central fact remains that Peterborough – whether town or city – in order to have her equipment of modern convenience up to the mark, must have an opera house worthy of its importance.” In February local business man William Fair travelled to Toronto “on business in connection with the Peterborough Conservatory of Music” in an attempt to raise money for the building of a new opera house. Fair apparently met with several former Peterborough “gentlemen” who had moved to the bigger city. He also spoke with theatre magnate Ambrose J. Small, who owned opera houses in Toronto, Hamilton, London, and Kingston and controlled a travelling circuit that covered much of the province, if not the country. According to the report, Small agreed to take a “large block of stock” plus lease the promised Peterborough building for ten years. Apparently other “former Peterborough gentlemen” now living in Toronto would help out financially as well, taking stock in a company formed to set up the theatre.

Examiner, Sept. 22, 1905, p.8.

Despite those promises, for the next little while the urgent need for a new opera house remained a dream at best. An Examiner editorial in March 1905 found it necessary to once again extol Peterborough’s “advantages” as being “far in advance of other towns, and most cities” – including the many “splendid” parks, the water works system, “the cheapest electric light and power in the province,” an excellent street railway system, summer resorts, and, looking ahead, the “splendid” armouries and “fine collegiate institute and separate school,” which were in the works. But, it added most importantly, “An opera house is one of our wants, and that will, it is hoped, soon come.” Later that month the Review added its own call for action:

It is doubtful if there is a town of the importance of Peterborough that cannot boast of a more modern, artistic and better located opera house than the one now in use. It has served its purpose and answered very well when Peterborough was about half its present size, but that day has long gone by and the period has come when action must be taken and something definite effected, as this progressive centre is about assuming civic garb and taking a step forward among the communities of the province. Surely some public spirited citizen or citizens, who have means to invest, will come forward with a definite proposal before another year passes, and do something in the line of meeting a long existing requirement.

“Other towns and cities of much less relative importance than Peterborough secure good attractions,” the Review concluded, “because they have adequate facilities, while this place is passed by, and the residents are not afforded an opportunity of extending their patronage to first class entertainments, which would, no doubt, be generously bestowed if the necessary stage and other accommodation could be supplied.”

Examiner, Oct. 5, 1905, p.8.

*****

Bradburn’s hall continued to draw good audiences for the occasional evening. In mid-January 1905 it was “packed to the doors” one Friday evening, with “not a vacant seat,” for a concert organized by the St. Peter’s Total Abstinence Society. On March 18 that year it was again “filled” to capacity “in every part” for a concert by the T.A.S., which was clearly a going concern in those days. Peterborough’s popular (and very good) 57th Regimental Band played there to a large house a week later. But still the need for a proper auditorium remained. When the Bijou Comedy Co. brought its play Under Two Flags to the Bradburn in February the notice stated quite frankly that it carting along its own “improved stage furnishings which will be made suitable to the inconveniences of the Opera House.” (Despite those limitations, the Bijou company returned the following fall.)

Examiner, Oct. 7, 1905, p.5. It was a busy spot right up until the loss of its number one position.

Peterborough, now a city of about 15,000 people, was still not getting the “good entertainment” that it deserved. As the Examiner editorialized in March 1905, “Peterborough has arrived at the stage of importance, when the humiliation of having to hold entertainment in a sort of superior barn like the present so-called Opera House is very greatly felt.” The city was without a place “where respectable dramas can be respectively put on or where a respectable concert can be respectably held. . . . Even the barn-storming dramatic companies that hold forth in the present Opera Hall make its dilapidated grotesqueries a butt of ridicule by their cheap comic man.” Peterboronians were having to go off to “the city” to “hear a good opera or good concert under tolerable conditions.” Finally, the editorial concluded: “It’s none too early now to begin moving for a new Opera House which can be ready for the opening of next winter’s entertainment season.”

*****

After such bleak prospects for so long, the “dream of years” would soon be realized. That new opera house — the Grand Opera House — opened at 284 George St. on Nov. 15, 1905.

Examiner, Jan. 4, 1908, p.8. This announcement says that the Assembly Hall was “under” the old opera house.

Even after the Grand Opera House became a reality, the old Opera House continued to offer the odd attraction. On November 2, 1905, it offered up the “greatest English humorist,” the “much heralded Mark Twain of England,” Jerome K. Jerome. A week later Judge Septimus J. Hanna amazingly drew in about five hundred people with an “interesting lecture” on the subject of Christian Science, “the religion of the Bible.” A “smoker” was scheduled for late January 1906, with a couple of boxing matches and the “brilliant club-swinging act” of a Teddy Andrews. In April 1907 boxing and wrestling were still being announced at “the old opera house.” But the original opera house disappeared from the city directory listings in 1907 (although in spring 1907, the entry for 332½ George was listed as “Assembly Hall”).

Yet the hall itself, now known as Victoria Hall, continued in use over the following decades. In the 1920s it was still the site of the odd concert and political meeting. In 1929, for instance, it was being “used by the Orange Lodges of the city and others desirous of presenting amateur plays on the stage.”

Review, April 7, 1915, p.8.

Review, April 23, 1915, p.2.

Examiner, Nov. 29, 1921, p.4.

Weekly Review, Sept. 22, 1921, p.6.

Examiner, March 8, 1926, p.1.

An entrance to the hall, with the “curious looking” loges above, 1969. PMA.

In 1929 Cathleen McCarthy, looking back at the history of “amusements” in Peterborough, reminisced about Bradburn’s Opera House and reflected on how it was once “the bright gathering-place for theatrical fans of the city.” In 1941 a city “oldtimer,” George Lynch, fondly recalled the many performances he’d seen in earlier years: from the Harry Lindley Stock Company and its East Lynne to John Griffiths in The Man in the Iron Mask to a “famous burlesque show” called Stars of New York, which had display posters “considered so modernistic” that the chief of police, George Roszel, ordered them to be covered. “Naturally such advertising brought out a record crowd, everyone expecting to see something spicy.” They were apparently disappointed, Lynch said: “The show was not at all objectionable, and it was one of the best and finest shows ever staged here.”

A visitor to the empty space of the opera house in 1938 found it had “a somewhat eerie appearance.” The large stage and the dressing rooms were still there. It had “a whole side taken up with curious looking low loges, which reminded us somewhat of the lower row of boxes in the old New Orleans Opera House, which is a replica of the Paris Grand Opera House.” This was the space that had witnessed spectacles such as the great staged tornado, the birth of the telephone and the phonograph machine, the early moving pictures — a place that had once been occupied by “a vast army of oldtime thespians, great melodramatic actors, Shakespeareans, etc.” and the likes of the Marks Brothers and famous orators and opera stars – and was now only a place of imagined ghosts. “We see a vast variety of great social events,” said the 1938 visitor, “with the ladies of Peterborough in their finest ‘decolletes’ and the young bloods with their soup and fish.” The wrestling and boxing matches of later years were not mentioned.

Remaining bits and pieces of the old opera house, 1969. This is the view looking down from the stage and showing the loges on the left. PMA.

In the 1940s the largely deserted auditorium was used as a training quarters by the Sea Cadets. PMA.

A view of the auditorium from the loges. The windows would have been looking out on George Street. PMA.

One long-time Peterborough resident, Gerry Armstrong, later remembered how after the auditorium had been partially dismantled the Sea Cadets used it as “their hall” – with the ancient outlines of the box seats still visible in the dim light. For anyone with a sense of history, it must have been something of a sad experience to run through military drills in that once-grand space.

Decades later, in 1973, around the time the whole block north of the Market Hall was demolished to make way for Marathon Realty’s new Peterborough Square development, one writer remarked that Bradburn’s Opera House “was one of the oldest theatres still standing in Canada and was certainly of historical significance.”

The streetscape of the 1950s. George Street at Charlotte, looking north, with the Bradburn building on the right, just above the Market Hall. PMA.

The Bradburn building, home of the opera house, c.1970. To the right, Market Hall. TVA.

The Bradburn block, c1970. TVA.

Sadly, this historic site, like many other architecturally astounding buildings in downtown Peterborough, went the way of the wrecker — along with the rest of that streetscape.

Below: a view of post-demolition, from the intersection of Simcoe and George streets, 1973, PMA. All that remained on the block was the Market Hall with its Tower, at the south end; and that was thanks only to an intensive public campaign spearheaded by heritage activist Martha Kidd.

![Examiner, Feb. 16, 1903, p.5. The show that broke the Bradburn’s back. It was “packing the Grand Opera House [in Toronto] every night.”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597b24ddcd0f68aa80828196/1591279486054-XZ7KSVU5KNEKH3JA6F7D/1903+Feb+16+p5+Bradburn+El+Capitan+%282%29.JPG)