1950s–60s: Theatres, They Come and They Go

Youngsters at a Coca-Cola promotion at the Odeon Theatre, 1956—57. Parks Studio, courtesy of the Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA) and Rick Mancini.

Advertising? Promotion? The interior of the Odeon Theatre, George Street, on a winter’s day in 1956—57. Would parents today have anything to say about their kids being taken to the movies to help promote a soft drink? It was a decade in which there was little concern about this sort of thing. Here the theatre’s downstairs is packed with school kids — many of them shouting and yelling and raising their arms with fingers grasping a bottle of Coca Cola. Attendants in white soda-shop uniforms are in the aisles and have been handing out the Cokes; a couple of ushers (with bow ties) can also be seen — and empty wooden Coke cases are in the aisle. Plaid shirts abounded on the boys (who seem to outnumber the girls, especially as seen down front); some boys wear rubber boots, but a couple in the front row are Boston Bruins fans and sporting quite nice cowboy boots.

A little while earlier the school kids had been neatly lined up outside — with the lineup extending past the Capitol Theatre right up to Charlotte Street. The Odeon Theatre, now renovated into the Showplace Performance Centre, continues to draw crowds for both stage acts and movies (especially at the annual ReFrame Peterborough International Film Festival), but without offering free Cokes.

For a short moment, five downtown movie theatres

“30 Years Ago, There Were Four Theatres Catering to Entertainment Needs of City,”Examiner, Dec. 15, 1947, p.10 (a look back on the occasion of the opening of the Odeon).

The Peterborough movie-going history of the 1950s really began in late 1947 (decades are by no means faithful to strict determination). Within the space of about a year Peterborough had two upstart modern theatres side by side on George Street: the Odeon (1947) and Paramount (1948). With these added to the Capitol, Centre, and Regent, the city now had five theatres serving a population of just over 44,000.

In 1947—48 that plentiful choice of theatres lasted only for a year and a half. The Regent closed at the end of May 1949, cutting the number back to four. The Centre closed in 1956, followed by the Capitol in 1961. In the end only two would be left standing.

*****

The arrival of the Odeon and Paramount

The Odeon opened on Tuesday, Dec. 16, 1947, with a British film, Green for Danger. Well before that, in May 1947, excavation had begun on the lot just next door. The owners, Famous Players Canadian Corporation, took out a building permit in August 1946. Famous Players had owned the site at 286 George St. N. and been contemplating erecting a theatre for several years, but were held back by wartime restrictions. The Paramount opened officially on Saturday, Dec. 4, 1948.

Examiner, Dec. 3, 1948, p.13. The Paramount, with all the modern conveniences — lots of light coming into the lobby from front windows on George Street (like the Odeon), a concession stand, even a “crying room” with accommodation for 18 mothers and their babies (which could double as a party room). With a substantial nod to civic rectitude, proceeds from the first night’s take went to the local Rotary Club. Famous Players now had three theatres in the city, with the Paramount joining the Capitol and Regent.

Examiner, Dec. 3, 1948, full-page ad. Look at that imagined crowd! The Crosby-Fontaine movie had “scenes from your own Canadian Jasper Park.”

Less than a year after its opening — and perhaps at least partly because of the British competition at the Odeon — Famous Players (and thus the Paramount) announced that it too was going “British.” One ad (Oct. 8, 1949) listed the British films that the theatre would be showing in the near future. But, as at the Odeon, the trend did not take a full grip on exhibition and U.S. movies continued to predominate.

Examiner, Dec. 4, 1948, p.7. Opening day at the Paramount — but also on offer, a full page of entertainment in other city venues. The Capitol was screening one of the best film noirs ever, Out of the Past (1947). Bing Crosby — at both the Regent and the Paramount — Abbott and Costello, Hope and Goddard. Lots of dancing, if you’d rather do that — and you could take a taxi. On radio, in case you wanted to stay home, the Aldrich Family and Peterborough’s own Humphrey Sisters.

Examiner, Oct. 8, 1949, p.7. A short-lived promise of British films at Famous Players theatres.

The Peterborough Drive-In Theatre

Examiner, July 31, 1948, p.9.

Around the same time, in quick fashion, came something a little different. Drive-in theatres – complete with busy concession booths for snacks and playgrounds for children – became a North American phenomenon in the 1930s and 1940s; only a few of them survive today. Peterborough had outdoor movies as early as 1905, in Jackson Park. Now, in 1948, it had another outdoor experience: the Peterborough Drive-in was located just north of the city, on the west side of what was then Highway 28 going up to Lakefield — a spot that is now a parking lot next to a Giant Tiger outlet. With a drive-in theatre, parents had no need to find a baby sitter. Children under 12 had free admission. The large lot serving the drive-in was called “Skyland Park.”

Left: Examiner, July 30, 1948, p.9. Right: Examiner, July 31, 1948, p.9. The owner initially was Park Drive-In Theatres, purchased by Toronto financier A.C. Cowan in 1948; in 1951 it was said to be Peterborough Drive-In Theatres Ltd. In 1963 Twinex Century Theatres Corp. took over.

Examiner, May 25, 1948, p.7. All five movie theatres, plus a drive-in. At the Odeon, a short, Canada Calls.

All the above ads, Examiner, April 9, 1949, p.7. This was the day I turned five, and was already in love with the movies, thanks to my family. At the Centre, with Pagliacci (the full title was Laugh Pagiacci, from Italy-Germany [1943], released in North America in October 1947), manager/owner Harry Yudin brings in some culture off the beaten path, as he did several times (with tickets exclusively on sale at the Tem Travel & Ticket Agency, next door to the Capitol Theatre). The Odeon offers special seats for the “Hard of Hearing.” The Paramount pushes its “Exclusive Reviewing Room” (originally called a “crying room”). Wake of the Red Witch returned a few years later to the Capitol, because I saw it there one Saturday afternoon — with its surprising moment at the end when the hero, John Wayne, drowns in his deep-sea helmet.

Examiner, May 27, 1949, p.7.

The closing of the Regent

Examiner, May 27, 1947, p.7. Everett English remembers his afternoons in the 1940s as a youngster at the Regent – and his experience of “mice and rats running across his feet.”

Examiner, May 28, 1949, p.7.

Examiner, May 28, 1949, p.7. The Regent closes. Its Foto-Nite moves to the Capitol.

Examiner, May 28, 1949, p.7. Top left: the Regent’s last picture show: The Corsican Brothers was an old movie (1941) based on the Alexandre Dumas novel; and the Hopalong Cassidy movie Riders of the Deadline (1943) had Robert Mitchum in a small part. Just down the street Mitchum was in a featured role at the Centre. Robertson Davies had commented rather bleakly on Corsican Brothers when it first came to the city in February 1942: “It gives Douglas Fairbanks Junior a chance to play both himself and his brother. . . . Mr. Fairbanks is beside himself, literally, a great part of the time. So are the audience, for they can never tell which is which, although they are fully conscious that both are the same.” Despite this, The Corsican Brothers played at least three times in Peterborough: its first run, at the Odeon in September 1948; a second run at the Centre in November of that year; and finally at the Regent.

Examiner, May 28, 1949, p.7. Now, at the Capitol, it is “Photo-Nite,” not “Foto-Nite.”

Moving into the 1950s — with a drive-in and four theatres (including a renovated Capitol, with reduced prices)

Examiner, Jan. 26, 1950, p.5. The Capitol, the closest thing the city ever had to a “movie palace,” was no longer the premier first-run theatre in town — and lowered its prices. It had its Photo-Nites and, harkening back to the 1930s, its special offers for the “ladies,” and it featured films along the lines of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) or The Attack of the 50 Ft Woman (1958) and countless Randolph Scott westerns.

Peterborough Weekly Review, June 21, 1951, p. June 21 p.5. Among the renovations was the removal of the orchestra pit, the last vestige of the silent film days. Although it reopened as a “Famous Players Theatre,” with a single feature, the Capitol was soon leased to Twentieth Century Theatres, an affiliate of F.P. that specialized in second-run films and double features (and which also owned the Century Theatre, in Lindsay). The Capitol, now thirty years old, fixed itself up a little, as here — with its “attractive new candy bar” — and, in competition with the Centre, offered a cheaper alternative to the glitter of the Paramount and Odeon.

Examiner, Jan. 21, 1950, p.7. The Capitol, with what seems like a throwback to the audience-drawing gimmicks of the Depression era.

Following the audience boom of the early to mid-1940s, attendance had already begun to decline after 1946, even before most people had television. Radio had its own boom period in the late 1940s as an entertainment that could be consumed at home. Television substituted for radio only after 1953 or so. The growth of the suburbs and the “automobility” of the postwar period also played a part. People were more mobile, had more leisure-time choices. With the baby boom there were more children around to care for — and in good weather there was always the drive-in.

To draw crowds, theatre managers once again went fishing with special, almost magical, lures. The Capitol focused on “ladies” setting up in new homes. At the Paramount, newly engaged couples were apparently all “agog” at the offer on hand.

Peterborough Weekly Review, March 9, 1950.

Peterborough Weekly Review, March 23, 1950, p.4.

Examiner, May 21, 1951, p.7. Parents had a duty, so they said, to take their teenagers to see Not Wanted. The drive-in had a whole lot of stuff on offer.

Examiner, Oct. 24, 1953, p.7.

Examiner, Oct. 24, 1953, p.7. Showing at the Capitol, two films released eight years earlier, in 1945. Film noir and the atomic bomb: it needed to be protected?

Snack bars make the scene . . .

Motion Picture Herald, Oct. 13, 1951, p.35.

Motion Picture Herald, July 2, 1955, p.52.

The age of the money-making concession stand had truly arrived — coinciding nicely with both the impact of television (you could never have popcorn at home quite as good as the popcorn at the movies) and the free flow of Coke and Pepsi promos.

Examiner, July 11, 1955.

Motion Picture Herald, March 12, 1955,p.33.

Motion Picture Herald, Oct. 8, 1955, p.42. “Please do not take drinks to seats.” How long did that last?

Apart from food and drink and drive-ins (which specialized in food and drink), exhibitors tried out 3-D, CinemaScope, VistaVision, Cinerama, Panavision, and other novelties. Technicolor became the standard. 3-D had a short life as a box-office attraction, but CinemaScope, introduced by Twentieth Century-Fox, proved a significant stimulant, and many theatres changed their standard screens for wider ones. The Centre was the first theatre to make the switch, in October 1953, quickly followed by the others.

Examiner, May 25, 1953, p.7. The first 3-D movie to be shown in Peterborough appeared at the Centre, followed quickly by a bigger 3-D attraction, House of Wax.

Examiner, Nov. 29, 1955, p.7. Cinemascope at both the Centre and Paramount.

Elvis and the age of rock ‘n’ roll arrive at the local motion picture show

Left: Examiner, Dec. 17, 1956, p.7. Elvis is announced.

Above and right: Examiner, Dec 31, p.7. I was there to see Love Me Tender for a teenage-packed showing one afternoon during the Christmas holidays. Someone who was also there said, “I’m not sure how much I heard with all the screaming!”

You could see the movie and buy the record at Cherney’s Record Bar, a stone’s throw across the street, kitty-corner on the south-west corner of George and King.

The Centre Theatre, too, goes down

Despites its recent attempts to keep up — a snack bar, 3-D movies, a wider screen — by the summer of 1956 the Centre Theatre, the once “worthy addition to Main Street” and at the time the city’s only independently owned theatre, was gone. It was always difficult for an independent to get the best attractions, and in recent years the Centre had screened low-budget or second-run movies (including B Westerns). It was hard to compete with the newer Odeon and Paramount theatres, or even the aging but larger Capitol. I remember going there, and it must have been not long before it closed, to see a cowboy “B movie” triple bill one Saturday. It was still better to be able to see those movies in a crowd at the theatre than at home on the 17-inch General Electric television set. The theatre closed after its last showing on August 18, 1956.

Examiner, Feb. 7, 1959, p.7. Motion pictures in the comfort of home: Roy Studio home rentals, and movies on television.

Examiner, Oct. 3, 1960, p.34. Three theatres.

Et tu, Capitol?

Examiner, Aug. 19, 1961, p.7. The Capitol’s closing show, with its old movies (Winchester ‘73, 1950, and Criss Cross, the film noir, 1949) — and closing note of thanks to its faithful patrons.

Examiner, Aug. 19, 1961, p.9. The Capitol building would be sold “on the stipulation that it is not reopened as a theatre.”

In August 1961 Famous Players took over the Capitol from Twentieth Century Theatres and closed it. Peterborough’s Theatre Row was now missing some bright lights — although the empty Capitol Theatre space was still there for years.

Examiner, Dec. 30, 1961, p.13. The view up George Street at Christmas 1961. Today, Curry Village is one of the occupants of the old (but renovated) building. Note the presence of Ray Judd, perhaps the best softball pitcher ever to play in the city.

A shift on the corporate front, and a change in mood: from Elvis the Pelvis to sex and The Graduate

In August 1961 the two giant chains, Famous Players and Odeon, decided to pool their Canadian houses. From Aug. 19 Odeon Theatres of Canada would be operating both Famous Players’ Paramount Theatre and the Odeon. Famous Players had also purchased the Capitol, previously owned and operated by Twentieth Century Theatres, but would not reopen it. That left just two theatres operating in Peterborough (and, in summers, the drive-in). The population of the city (“and environs”) was now about 52,000.

Sometime in the 1960s an Examiner article pointed out that, according to the local theatre manager, the most popular movies in the city were the Elvis Presley pictures being churned out on a regular basis. I suspect the likes of the beach party series were a close second.

Left: Examiner, Dec. 29, 1962, p.20. Middle: Examiner, July 20, 1965, p.18. Right: Examiner, Sept. 1, 1965, p.30.

Left: Examiner, July 2, 1965, p.25. Middle: Examiner, May 4, 1965, p.20. Right: Examiner, May 11, 1964, p.20.

Examiner, March 19, 1964, np. Courtesy Ken Brown.

You might not have been able to take in Road to Sin (1960), but if you were really lucky, and of a certain age . . . you might get to go to a theatre party! And the local Foster’s restaurant and drive-in could sell the relatively new product, Kentucky Fried Chicken. The ad even offers advice for those who had no children.

In contrast, for the older crowd the screen offerings of the 1960s were beginning to show a certain more sexually provocative strain, with “adult entertainment” coming into its own. The Production Code that had been established in the 1930s was now having a tougher time of it. The Motion Pictures Association of America (MPAA), the body that ruled over such things, replaced the Code in 1968 with a ratings system. As a recent (2021) New Yorker article on the making of Midnight Cowboy (1969) put it, by the mid-1960s, “The conditions for a new kind of Hollywood movie were on the rise.” But the shift in cultural temperament was not entirely new. The clip below (next to the Dr. No ad) gives a glimpse of a news item: in his regular syndicated entertainment column, the first of a five-part series, Bob Thomas wrote about how the “Sinful, Oversexed Movies [i.e. of the present] Began with Gay 90s Kiss” and went on to Clara Bow’s “sexy roles” of the 1920s.

Left: Examiner, May 1, 1963, p.20. Middle (two columns), Examiner, Aug. 3, 1965, p.20. Right: Examiner, Aug. 17, 1965, p.18. The partial column next to the Dr. No ad gives a glimpse of a news item: in his regular syndicated entertainment column, the first of a five-part series, Bob Thomas wrote about how the “Sinful, Oversexed Movies [i.e. of the present] Began with Gay 90s Kiss” and went on to Clara Bow’s “sexy roles” of the 1920s.

. . . and somewhat more serious, award-winning fare.

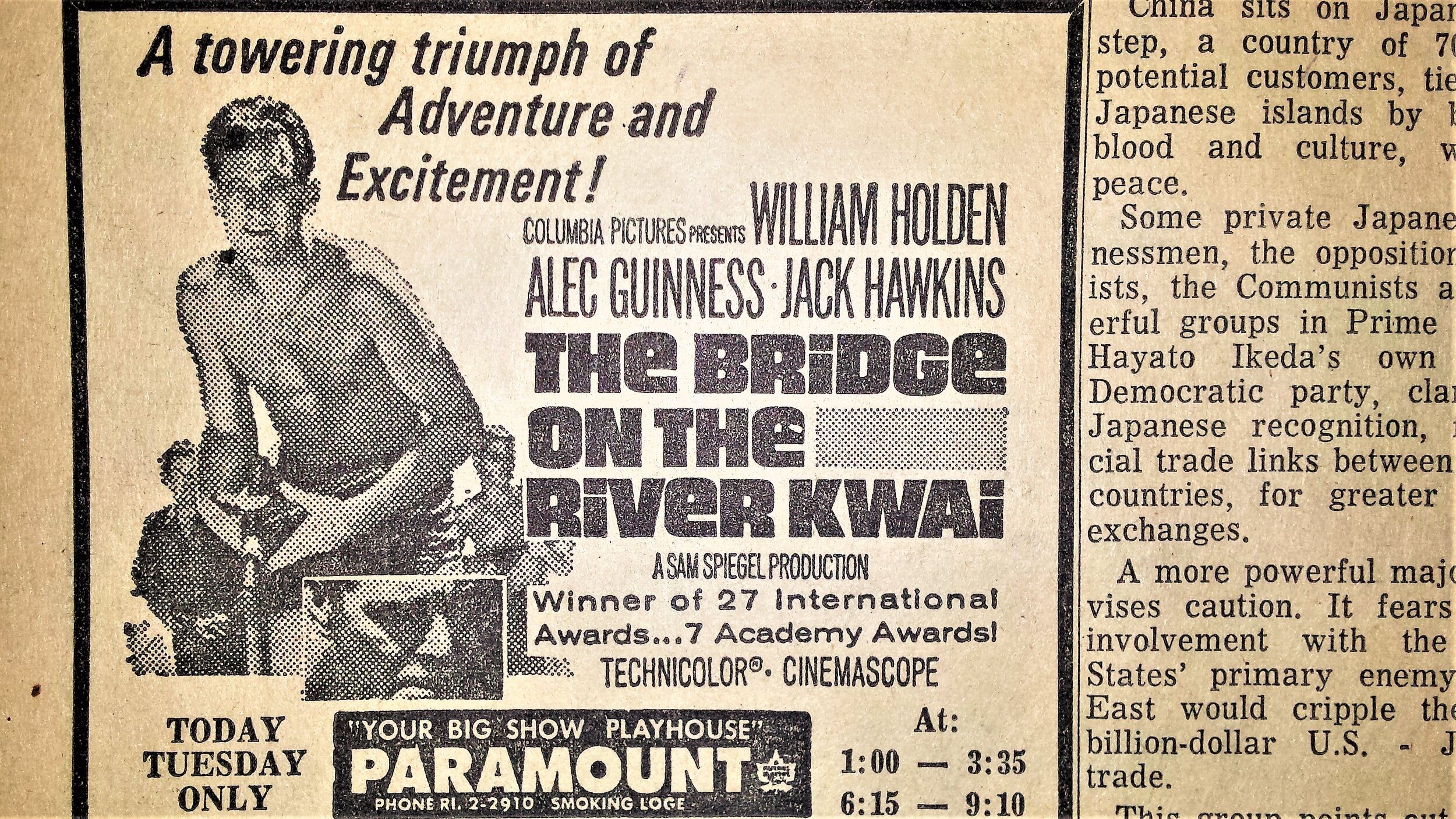

Examiner, Oct. 19, 1964, p.34, in a re-run of the 1957 film.

Left: Examiner, March 26, 1965, p.24. Right: Examiner, July 2, 1965, p.25. Quite illicit affairs. In the article on “Sinful, Oversexed Movies” (see above) Bob Thomas takes Elizabeth Taylor (“as a Bohemian artist”) to task for posing “almost nude for a statue” before the gaze of the episcopal minister played by Richard Burton.

A significant shift occurred in film-making (and thus film-going) in the second half of the decade or thereabouts: a new generation of film-makers, the partial breakdown of the studio system, the move towards a “world cinema” and the hefty influence of foreign films (and especially the French new wave), technical innovations and new aesthetic sensibilities, and more personal, edgy, anti-authoritarian styles and content — all of it more than once dubbed “a revolution.” With a new more general interest in film as art, there was an increased appetite for movies that were not so readily seen at the theatres. Film societies sprang up, including a short-lived Peterborough Film Society (fd. 1960, drawing audiences for a few years) and the Trent Film Society (fd. 1967, and still going strong). Repertory theatres and film festivals would follow.

Examiner, April 15, 1967, p.20. Alfie is just one example of many, and by no means the best. Others examples abound: Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Darling (1965), Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Blow-Up (1966), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Midnight Cowboy (1969) — plus the work of Ingmar Bergman, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Agnès Varda, to name only a few. Before Blow-Up (according to writer Douglas Gomery), MGM had never released a film not approved by the Production Code. Alfie was a commercial film (held over!) but its hero was not so much a hero as a louse — and there he was, talking to the camera (Brechtian style). The films of the time were still largely male concerns — feminism, the second wave, had yet to arrive (despite the appearance of The Hellcats, a couple of ads below). This new wave of cinema still tended to be buried alive amongst the standard presentations.

Another big change: the coming of Sunday movies. Following municipal elections in December 1964, Sunday movies began on Jan. 3, 1965. Total votes were 7,212 for Sunday movies and 4,485 against. In March Howard Binn, the Paramount manager, declared that the response in Peterborough to Sunday movies was “amazing.” They were attracting both city people and large numbers from surrounding districts. The Odeon manager, Fred Dorrington, had just moved to Peterborough in January from a theatre job in Toronto. He told the Examiner: “I find that Sunday movies in Peterborough are as well patronized as in Toronto or elsewhere.”

Examiner, May 24, 1968, p.24. For a new generation of film-goers.

Examiner, March 26, 1965, p.25. Of course, you could also stay at home and watch TV.

Below: The Entertainment page in mid-1968, and not all that revolutionary. Elvis at the Lindsay Drive-In. Not one but two Debby Reynolds movies (she had appeared in her first film twenty years earlier). The regular Bob Thomas Hollywood column, and James Bacon on a new star. CBC will put the Olympics on TV. “Ask Andy” will answer your question about Borax. Entertainment is no longer with the sports pages, at least here; but it manages to vie with the cartoon strips.

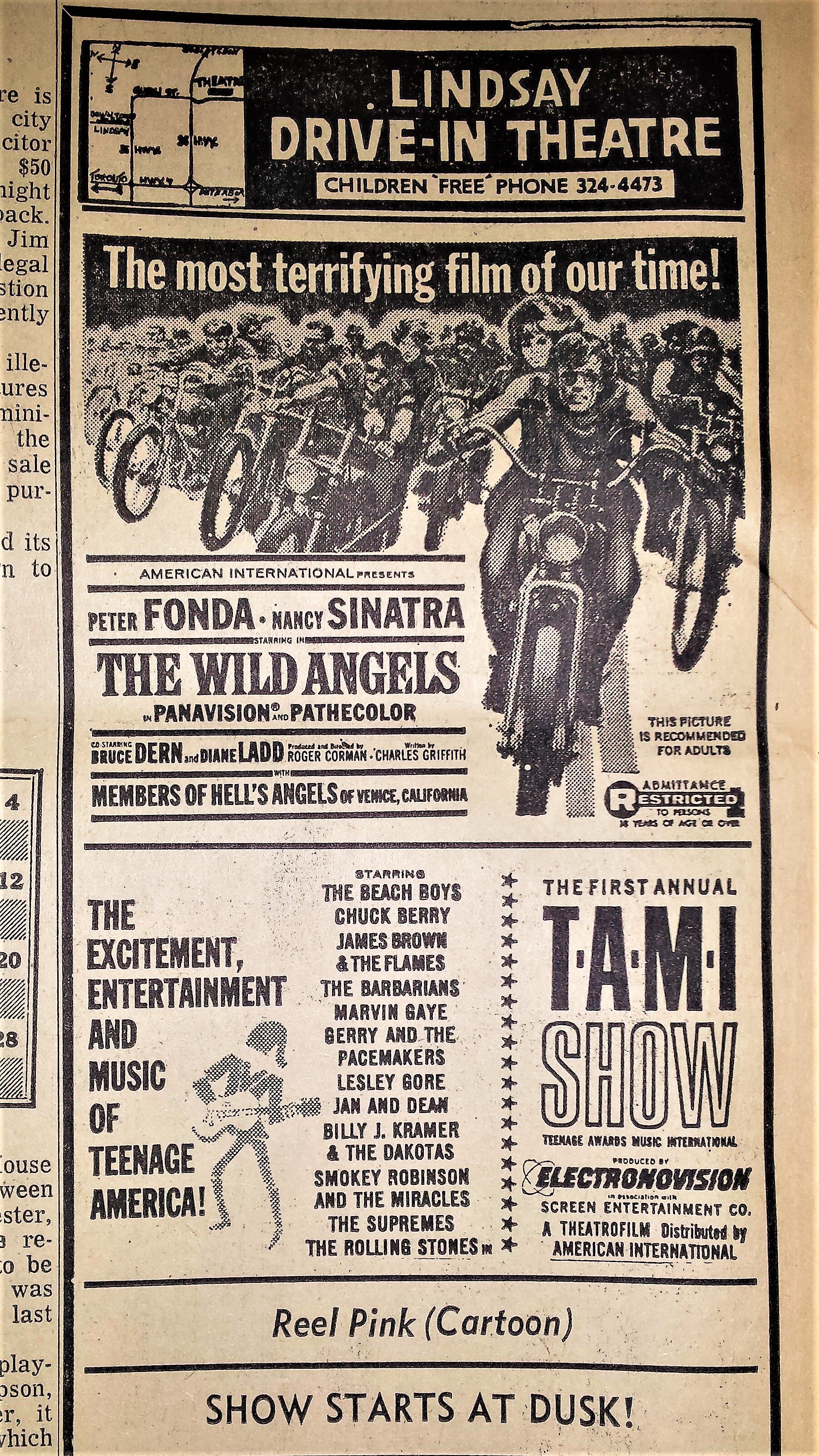

Examiner, July 24, 1968, p.26. With the two main theatres now under the same management, the Paramount tended to have the big hits, the Odeon the less cherished pictures, and double features. At times the drive-ins had the more sensational or lurid — and (in The Tami Show) almost hip — stuff.

Ads, Examiner, May 24, 1968, p.24. Sensational shows at the drive-ins. The Wild Angels (a Roger Corman picture) was certainly not “the most terrifying film of our time!” But The Tami Show would have been well worth the ride — to see those historic performances by the popular musicians of the time. Although attendance for children was still free, only adults were encouraged to attend.

Added to the mix in 1968: a second drive-in theatre

Examiner, Sept. 18, 1968. The Mustang Drive-in Theatre opens Sept. 19, 1968. Room for 775 cars, and one of the largest screens in the country, or so it was said. Part of a chain owned by G.T.I. Drive-in Services. Ownership later changed to the Premier Operating Company, the largest drive-in theatre firm in Ontario, and even later to a series of independent operators.

A by-law in Cavan Township prohibited Sunday opening. The original manager was Al Ford, who stayed at the job for twenty years. The Mustang closed in September 2012.

Examiner, Sept. 18, 1968, p.34.

Teaser ad, nd, Mustang Theatre, Examiner, August-September 1968, www.ptbocanada.com.