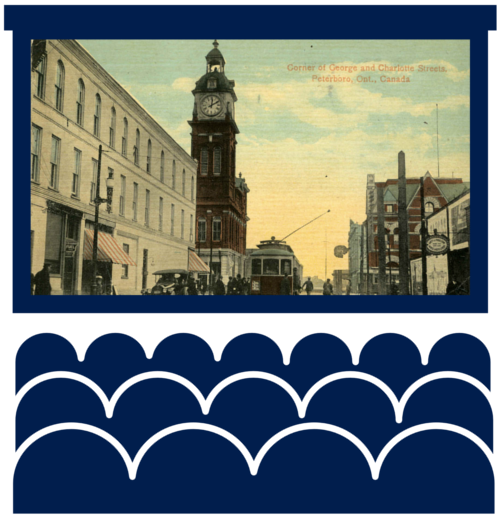

Royal Theatre, January 1909

The Royal Theatre, c.1909, Peterborough Museum and Archives (PMA), 2000-012(629-1).

The Royal Theatre, with this dazzling front entrance, opened at 332 George Street (on the east side between Charlotte and Simcoe) just before Christmas in 1908.

Examiner, Jan. 25, 1909, p.1. “Scotch Night” at the Royal, with the film Mary Stuart.

This Roy Studio photo was taken a month later, towards the end of January 1909; it shows on the far left and right sides of the doors, however dimly, a poster for “Mary Stuart, A Drama,” which played at the theatre from Monday, Jan. 26 to Wednesday, Jan. 27, 1909.

Inside the door, to the left of the lobby, was a mechanical piano that became part of the lore of the theatre. A sign on the ticket booth says, “Pictures Changed Every Day,” which was standard practice of the time. Although Mary Stuart was held over for three days, new pictures showed with it every day.

Over a high front arch the name – The Royal Theatre – shone out brightly with the help, it was said, of two hundred electric lamps. The entrance proper was “protected from the gales of winter by plate-glass front doors.” Inside, the walls of the lobby on either side of the ticket office had diamond-shaped plate-glass mirrors. The walls of the theatre itself were divided into framed panels “with hand-painted devices.” The theatre had seats for about 600 people.

The Royal’s owner was Mehail Pappakeriazes, who was born in Greece in 1878 and immigrated to Canada in 1904. In Peterborough in late December 1905 Pappakeriazes established a cigar store and billiards hall (and shoe shine parlor) at 332 George Street – and quickly became known “by his many friends” around town as “Mike Pappas.” He was soon advertising himself as the city’s “Leading Cigar Dealer.” Less than a year after he had set up his store an Examiner writer noted that his “enterprise has been very marked since he arrived in the city.”

For a year or more Pappas contemplated adding to his business ventures by setting up a motion picture theatre. He eventually found a potential site at 348 George, in a vacant building near his cigar store; the space had previously been occupied by the offices of the Times Printing Company.

After spending an estimated $3,250 on renovations (over $70,000 in 2017), Pappas opened his theatre doors to the public on Saturday Dec. 19, 1908. Pappas announced: “These Films or Pictures will be seen by Peterborough people before any other audience in Canada. They show clearer and better pictures than the cheap hack pictures that pass from one theatre to another.”

Word was that the theatre was “filled to the doors” each evening of its first week.

Pappas chose where possible to give employment to local citizens. Starting out, the Royal had eleven male employees in all, with seven of them born in Peterborough and four in Toronto.

The automatically operated electric piano inside the door proved especially fascinating. “How does that work?” more than one visitor asked when the theatre had an open house shortly before opening. “Why, look at those keys, pounding away without anyone at the piano!”

A little speech that Pappas made to the “boys” in his employ shortly after opening offers a glimpse of both his theatre-business credo and of the people he saw as his prime patrons in those days:

Boys, I am going to see that ladies and children, who form a large proportion of our audiences, will never see a picture or hear a song that could be objected to by the most exacting, and I am sure from the experience of the past week or so since we opened that you are all backing up my desires splendidly. Remember boys, that children and ladies will always feel as comfortable as in their own homes.

In January 1909, a month after opening, Pappas presented “A Scotch Night” – declaring, “Scotchmen, especially, should not miss the beautiful pictures.” The program featured Mary Stuart, a recently released (Nov. 23, 1908) Pathé Frères film (drawn from the Victor Hugo novel) of “court life during the sixteenth century.”

Evening Examiner, July 10, 1908, p.1.

He scheduled Mary Stuart for Monday and Tuesday, Jan. 25 and 26, but on Wednesday he announced that “By request of several leading citizens unable yesterday to see the splendid Pathe film entitled Mary Stuart Queen of Scots” he would present the film again that day. He added, “This colored picture is a splendidly told story of Court life during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and will be explained as the story progresses.”

The last statement provides a hint of the standard practice at early silent film showings of having a “lecturer” explain the various scenes. It might have been particularly necessary for this film; a review in Variety remarked that Mary Stuart was “incomprehensible to anyone unfamiliar with the story.” That reviewer especially failed to appreciate the film’s “intended-to-be-gruesome” finale (in which Mary Stuart lost her head). A reviewer in the Moving Picture World trade magazine was also critical: “The only good scene is the first: the rest are perfectly absurd.”

Still, another writer in the same publication remarked more positively, “The audience was captivated and many will be pleased to see again this splendid film.” He noted, “If the manufacturers could give us more of these historical films they would teach history in a very interesting and effective way and parents would gladly open the purse string to send the children to shows where they can learn something” – although he went on to add a rather backhanded slap: “only let the historical facts be more accurate than in the one just referred to.”

Examiner, Feb. 26, 1909, p.1.

At 836 feet, Mary Stuart was about ten minutes long. A couple of other short films were shown with it each day. Monday had another Pathé film, The Fiddlers, 278 feet (July 1909), “A grand colored film,” and The Maniac Cook, 533 feet (January 1909, from Biograph, and directed by D.W. Griffith), which, the ad assured, “produces a laugh a minute.” Tuesday and Wednesday had different films announced: Carlo’s Revenge and Mr. Brown’s Prize. (I haven’t been able to trace either of these titles.)

Open that first year “morning, afternoon and evening,” the Royal also presented vaudeville attractions along with the short films. The pictures ran from ten o’clock in the morning until six in the evening, with vaudeville performances at three in the afternoon and seven in the evening. An early act was “the Great Selvin,” an illusionist (“one of the cleverest in this line”), with his company and various specialties. Another was “Mrs. Marguerite Walsh,” a noted Boston mezzo soprano, and her “little daughter,” ten years old, “already an accomplished singer.” Mrs. Walsh sang “comic songs” from the stage several times during a few evenings’ presentation of films. One of her songs, “The Stuttering Boy and the Lisping Girl,” proved particularly popular as she displayed her “rare histrionic powers, as well as being a gifted vocalist.” I'm left wondering: Would that song, if performed today, be acceptable, let alone popular?

For the first month or so the Royal also brought in “Mr. Beveridge Miller, Detroit’s Celebrated Tenor, Robusto, to sing illustrated songs. “A great vocal treat.” Miller’s songs over a week or two included “With You,” “Annie Laurie,” and “Nobody Knows and Nobody Cares.” A duet with Mrs. Walsh “elicited great applause.”

Sources: “New Theatorium Will Have Elaborate Street Entrance,” Evening Examiner, Sept. 21, 1908, p.7; “Building Permit Taken Out for New Theatorium,” Evening Examiner, Oct. 7, 1908, p.7; “Opening of Royal Theatre,” Evening Examiner, Dec. 18, 1908, p.8; “The Royal Theatre Was Opened to Large Crowds This Morning,” Evening Examiner, Dec. 19, 1908, p.13; “Presentation Made to Local Merchant,” Morning Times, Dec. 28, 1908, p.1; “30 Years Ago, There Were Four Theatres Catering to Entertainment Needs of City,” Examiner, Dec. 15, 1947 (which mentions that the Royal Theatre was “known for its mechanical piano”); Moving Picture World, Nov. 28, 1908, pp.422, 424, 433, 439; Richard Abel, Red Rooster Scare: Making Cinema American, 1900–1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p.131.