Wings: Watching a Movie at the Grand Opera House, 1928

“People come to the motion picture theatre to live an hour or two in the land of romance. They seek escape from the humdrum existence of daily life. . . . Here is a shrine of democracy . . .”

On Saturday, Feb. 24, 1928, a couple of young Peterborough boys went to the Grand Opera House to see one of the “big” movies of the time: Wings.

Thanks to Examiner reporter Cathleen McCarthy (who wrote under the byline of “Jeanette”), we have a rare glimpse of that movie-going experience.

*****

Wings opened in New York City in August 1927 and in Los Angeles in January 1928. It was a Hollywood silent-film extravaganza, at 139 minutes long (with an intermission). The most expensive film made to that date, it was the winner for Best Picture at the first Academy Awards presentation in May 1929.

The Paramount epic was known especially for its aerial combat sequences, experiments in colour tinting, and realism. It pulled no punches when it came to the nastiness of air-fighting and deaths, but had a conventionally romantic subplot.

The movie starred Clara Bow (the sensation of the time) and Charles (Buddy) Rogers, with Gary Cooper in a small role that launched his career. The plot revolved around two young American World War I fighter pilots, Jack Powell and David Armstrong, who came from the same small town but different social classes; they had a close but fraught friendship complicated by a love triangle.

When the film opened in New York, critics were generally impressed, including the writer in The New York Times: “This feature gives one an unforgettable idea of the existence of these daring fighters – how they were called upon at all hours of the day and night to soar into the skies and give battle to enemy planes; their light-hearted eagerness to enter the fray and also their reckless conduct once they set foot on earth for a time in the dazzling life of the French capital.”

*****

Wings arrived in Peterborough in late February 1928, showing to crowded houses at relatively high prices for just two days – a year before it received the Academy Award for “Best Picture, Production.” It did so well it was screened a second time a few months later, in June.

Examiner, Feb. 23, 1928, p.13. Wings would return in June for a second run — and would be the last film shown at the Grand Opera House.

The film first played at the Grand Opera House for two evenings, Friday and Saturday, Feb. 24 and 25, with a matinee screening on Saturday. Its “special augmented orchestra” was an added bonus for the audience. Examiner editor Fred D. Craig reviewed the film in Saturday’s paper, calling it “a wonderful picture.”

Cathleen McCarthy – or “Jeanette” – followed up a couple of days later with her own twist on the film – a very particular audience response – in an article headlined “He Sees Wings.”

Examiner, Feb. 28, 1928, p.3.

When McCarthy went to see the movie on Saturday afternoon, she sat near three youngsters: “a little boy, not more than seven years of age,” his brother, “and another small lad.”

It seems that she became as captivated by the boys as by the film.

In Tuesday’s paper she reported that “Half of the time” during this very long movie – “that is, in the air scenes” – the littlest brother was “on his feet.” He couldn’t sit still for all the excitement. But “the sentimental episodes” of the love scenes “left him cold. He sat quietly through them, evincing little interest.” As Jeanette wrote about the youngest boy:

‘There’s the girl’ was his only comment when the lady appeared. And he clung steadfastly to the belief that David and Jack were brothers. That’s why they were such pals, in his opinion.

He knew instantly what would come later on. ‘Watch the girl,’ he said. ‘She’s going to climb under the car.’ She did. ‘Now they’ll hit the car.’ They did, with one of their bombs.

The Germans were ‘bad guys’ and the two heroes of the picture were ‘good guys.’ They were also Canadians, instead of Americans, as the producers intended. ‘Watch the Canadians win,’ he said, every time that the camera depicted a triumphant advance.

‘There’s one of the good guys in the wee, white car,’ he announced triumphantly. ‘He’s going to get the bad guy’s balloon. Watch him get it – oh, lady, lady!’ (as the flames consumed the big gas bag). He read the sub-titles rapidly. ‘Weeks pass.’ His brother: ‘What passed?’ Little boy (impatiently): ‘Any weeks.’ They all subside, to brighten up again when the planes ‘strafe’ the German trenches.

‘Oh boy, look at ’em run! Look at the good guys smash the bad guys. Hurray!’ (as the tanks rumble over an energetic machine gun nest). ‘They’re all Canadians in that tank. It goes that way because they’re all drunk inside. Look at the rest of the Canadians coming along behind the tank so they won’t get killed.’

On a flying mission towards the end of the movie, David’s plane crashes down in German-occupied territory, but he evades the enemy and manages to steal one of their planes from an airfield to make his escape.

Later his pal Jack, trying to fly to the rescue, spots that plane with its German markings and shoots it down, not knowing David is in it.

The Peterborough boys had their own interpretation of this scene: “Gee, he killed his brother. Look at him yellin’ at the good guy and he can’t hear. Gosh, he killed him.”

With “the killing all finished” and “the good guy” apparently dead, Jeanette wrote, the boys “quiet down.”

Through the following scenes, which take place back in America after the war is over (and with the love affair being straightened out to a satisfactory conclusion), the boys are not at all animated. “As far as they are concerned, the picture is over.”

As it turned out, they were not alone in this tepid response. The New York Times reviewer quite agreed: “The last chapter, that concerned with the return of Powell to his home in this country, is, like so many screen stories, much too sentimental, and there is far more of it than one wants.”

The problematic delight in the glorification of war goes back to the beginning of motion pictures and is on obvious display here. But it is particularly interesting that these boys saw the American soldiers in a Hollywood movie as being "Canadian." I wonder if they had possibly seen the movie Ypres (U.K., 1925), which played in Peterborough in April 1926, or especially The Somme (U.K., December 1927), which had come to town just a month earlier, in January 1928? Both of those films, as quasi-documentaries, had featured Canadian soldiers, which might have led the boys to see all soldiers as equally Canadian.

And what impression would the exciting but bloody war scenes have had on these boys? (The love scenes apparently didn’t make much of an immediate impression at all, but then you never know . . .)

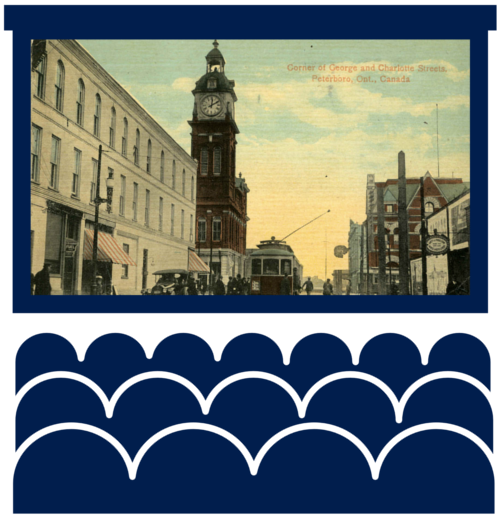

In any case “He Sees Wings” provides a rare opportunity to find out what it was like to be in the comfortable seats of the huge Grand Opera House on George Street and witness a major film event of the 1920s through the eyes and minds of youngsters (and someone at their side).

Sources: Mordaunt Hall, “The Screen; The Flying Fighters,” The New York Times, Aug. 13, 1927; F.D.C., “Wings,” review, The Examiner, Sat., Feb. 25, 1928, p.13; Jeanette, “He Sees Wings,” The Examiner, Tues, Feb. 28, 1928, p.3; John F. Barry and Epes W. Sargent, “Building Theatre Patronage (1927), in Moviegoing in America, ed. Gregory A. Waller (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 2002), p.110.

![1928 Feb Wings_poster[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/597b24ddcd0f68aa80828196/1512331778531-45FRDX02XTHAJQYYHVY7/1928+Feb+Wings_poster%5B1%5D.jpg)